Latest News

Aaron Copland at 125: A Defining Musical Friendship

Posted November 18, 2025

Aaron Copland at 125: A Defining Musical Friendship

by Michael Boriskin

November 2025

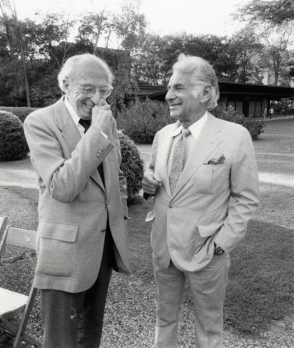

Photo: Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein at Tanglewood, ca. 1970s. Photo by Walter H. Scott, courtesy of the Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives.

Photo: Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein at Tanglewood, ca. 1970s. Photo by Walter H. Scott, courtesy of the Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives.

November 14th is a banner day here at Copland House, Aaron Copland’s National Historic Landmark residence one hour north of New York City and home to an award-winning creative center for American music. That was the birthday of our legendary namesake in 1900 in Brooklyn, NY (making this year his 125th!). But by some kind of cosmic harmony, November 14th also held special, double importance for Leonard Bernstein. As LB fans and devoted readers of Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs know, that was the day in 1943 of young Lenny’s momentous, last-minute substitution for Bruno Walter on the New York Philharmonic’s podium, which launched the wildly-gifted 25-year-old dynamo into the musical stratosphere. Less-widely known is that November 14th was also the day in 1937 when teenaged Lenny unexpectedly met Aaron Copland in person for the first time. Serendipitously, they were sitting next each other at an Anna Sokoloff dance recital in New York City, when they were introduced by poet Muriel Rukeyser. Copland was already a musical hero to Bernstein, who had studied and performed the still-new Piano Variations, a formidable work destined to become a cornerstone of the 20th-century piano literature. Aaron invited Lenny to a post-recital birthday party that night, and the encounter marked the start of a deep personal and professional relationship that lasted for the rest of their lives. (Though Copland was 18 years older, they passed away within six weeks of each other in 1990.)

Separated by the distance between Harvard (where Lenny was still an undergraduate) and New York, their relationship first developed through a correspondence that quickly became wide-ranging, showing their mutual admiration, respect, and affection for each other. (Letters from Copland were addressed to “Dear Pupil,” “Lennypenny,” and “Lensk;” and from Lenny, “Aaron Excelsus,” Astral Aaron,” and “Earth-Scorcher, Location-Adorner.” In their early correspondence, Aaron wrote as a counselor, guru, and advisor, giving guidance on Lenny’s college thesis, providing professional recommendations and connections, and serving as a sounding-board for the abundantly-gifted young artist; Lenny’s letters were as all-encompassing as expected, discussing people, projects, places, and poetry (and those are just the topics beginning with “p!”)

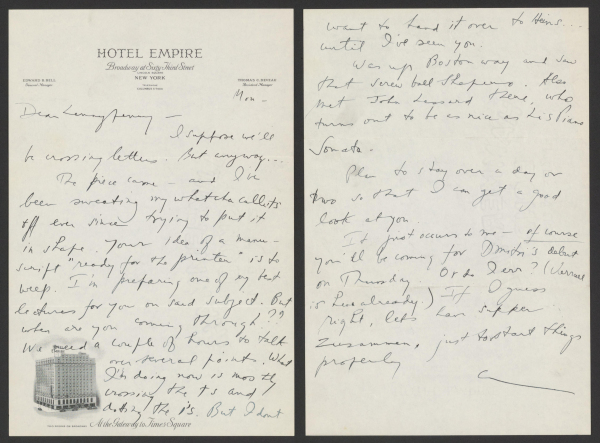

Photo: Letter from Aaron Copland to Leonard Bernstein, n.d., courtesy of the Library of Congress Music Division.

Photo: Letter from Aaron Copland to Leonard Bernstein, n.d., courtesy of the Library of Congress Music Division.

But within a couple of years, Lenny saw Copland as “my first friend in New York,” after the newly-minted Harvard graduate moved to “the city that never sleeps,” and musical projects and activities involving both of them began to develop. The first published works bearing Bernstein’s name were the solo and two-piano transcriptions that Aaron asked Lenny to make of El Salon Mexico – only a half-dozen years old and already frequently appearing on orchestral programs; barely in his twenties, Bernstein’s idiomatic piano versions brilliantly captured the brashness, kaleidoscopic colors, and clarity of the original. Not long thereafter, Bernstein conducted and directed a production in Boston of Copland’s then-recent children’s opera, The Second Hurricane. When Bernstein began working on the ballet music for Fancy Free withJerome Robbins, Copland made a home-recording with Lenny, rumbling though excerpts for four-hands that the choreographer could use when creating the dance. Within a few more years, Bernstein, around 30, was not only conducting many of the first performances of one of Copland’s largest works, the now-classic Symphony No. 3, but was also tussling with Copland over substantive creative issues, especially including a back-and-forth about an important cut in the piece. (Copland initially “thought it was pretty nervy of Lenny to take it on himself to make a cut,” but soon came to agree with him!)

The decades-long Copland-Bernstein relationship evolved naturally over time, and may well have been one of the most consequential in 20th-century American musical history. When Lenny was starting out in the 1930s, he often called Copland the closest he ever came to having a real composition teacher. Copland was a generous yet rigorous mentor to young Lenny, as he had been for so many other composers before and after – a musical beacon, role model, and standard-setter, as well as an effective advocate and generous colleague. As Bernstein garnered prestigious conducting engagements and positions around the world, beginning in the 1940s and 1950s, he was able to provide important and increasingly-visible platforms for a wide range of Copland’s music, often placing the composer and his works in the literal and figurative spotlight via concerts, recordings, commissions, special projects, and nationwide radio programming and telecasts.

Aaron and Lenny always remained very close. Late in their decades-long relationship, Bernstein called Copland “my master … idol … sage … shrink … guide … counselor … elder brother … beloved friend.” Copland, ever quiet and measured, viewed Bernstein as “the conductor who has always understood my music almost intuitively,” and wrote of the “deep satisfaction it is for me to know that we’ve sustained our feeling for each other all these many years. It’s a joy … and just imagine what it means to me to see you prepare and conduct my music with such devotion and love and musical sensitivity – for that alone I am forever in your debt.”

-----

Named one of Musical America’s “Top 30 Professionals” (2023), pianist Michael Boriskin performs in over 35 countries, records extensively, and serves as Artistic and Executive Director of Copland House.