Latest News

Felicia Montealegre: Mid-Century Enigma

Posted January 25, 2024

Felicia Montealegre: Mid-Century Enigma

By Hannah Webster

Felicia Montealegre Bernstein was many things: an actress, mother, wife, pianist, amateur painter, and social activist, to name just a few. But beyond those basic facts, her life and her personality become a murkier paradox.

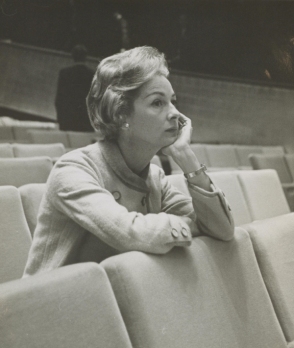

Felicia, pensive, at Philharmonic Hall. Photographer and date unknown, photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

She had an acting career and was an independent, headstrong person, yet also married a public figure and started a family in the infamous postwar “utopia” of the 1950s. Articles about her from that era often paint her in a very stereotypical “gorgeous woman, married to the maestro” light. News outlets dined out on describing her outfits and beauty: “Elegant in black––Mrs. Leonard Bernstein in a sleeveless dress, black mink hat[,] and pearls,” (New York Post) or even in the case of work engagements, “concert narrator with charm/beautiful lady narrator” (The San Francisco Examiner). This language is a reflection of its era, but underneath these all-too-familiar tropes most women also desperately wanted to be recognized for more than their looks and their allure.

Felicia was constantly vacillating between these ideas, vigorously eschewing societal expectations while simultaneously also personifying them. How did she manage these extremes? Perhaps the short answer lies in her chameleon-like personality. Her boldness, for example, took her far: she bravely moved to New York in her early 20s to study piano, and barely knew the place when she arrived at her Greenwich Village basement apartment. A true New Yorker-to-be, Felicia exhibited a cool head and dogged persistence that helped her succeed from the beginning. She started night classes for acting shortly after her arrival and switched careers without telling her parents. They didn’t find out until she’d made her Broadway debut in Ben Hecht’s Swan Song less than five years later, a remarkable achievement for someone so new to the game.

Felicia’s marriage to Leonard Bernstein was also a bold choice. The two were a likely pairing in many ways; they were warm, witty, caring, musical people, and both intelligent to boot. But their combined strong wills often had them living two different lives at the same time. They worked hard to convince each other their relationship was “Correct.” Shortly after they wed in 1951, Felicia wrote Lenny and said, “And let’s relax in the knowledge that neither of us is perfect and forget about being HUSBAND AND WIFE in such strained capital letters, it’s not that awful!” (Simeone, p. 294). Both felt a keen anxiety about the arrangement, as further evidenced by Leonard Bernstein’s opera Trouble in Tahiti that explores the challenges of gender stereotypes and marital conflicts in the aforementioned 1950s postwar era. Tellingly, he started composing the work on their honeymoon.

The trepidatious couple starting their honeymoon, September 1951. From their wedding album, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Given that mutual disquiet, their relationship deserves a more nuanced look. In 1955, when she and Lenny were interviewed on the CBS television program Person-to-Person, Edward R. Murrow asked, “Felicia, what about you? Are you engaged in other things besides acting?” Her response is elusive: “Well, Ed, it gets very hard to do much more than take care of this household. My husband, children…and acting takes the rest of the time that’s left over.” That could signify quiet resentment, or a genuine love of caring for her family and being available to them…or all of that at once.

Felicia with her family, 1960s. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

This duality paradox also applies strongly to visual appearance. For as much as it makes one itchy (at best) to hear her being described “beauty first,” Felicia celebrated her own appearance and was proud of it. She worked hard to hone her aesthetic, as receipts from Bonwit Teller and Bergdorf Goodman confirm. Her outward appearance was always polished and striking, and she made fashion statements in the classical music world when attending her husband’s concerts. But as usual with Felicia, there was more going on. In a 1958 interview with The New York Times, she said, “Fads can become serious. Some people may attend to show off their mink, find they enjoy the music[,] and become devoted to the Philharmonic” (Burton, p. 298).

Her desire to help others and champion causes produced beneficial results, but in at least one case also had devastating personal consequences. The infamous Black Panther fundraiser in January of 1970 turned ugly when Felicia’s aim to raise money for the Panther 21’s families was contorted and reduced to “radical chic.” But she continued her efforts nonetheless, and spent much of her adult life fighting for human rights in the United States with the ACLU and Another Mother for Peace. She also co-authored a New York State parole system report, and worked behind the scenes with Amnesty International in her native Chile.

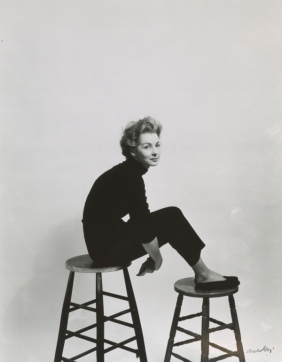

A young Felicia Montealegre, posing on stools. © The Richard Avedon Foundation.

Felicia is but one microcosmic example of the delights and struggles of being a mid-century woman in America. She passed away in 1978, at the far-too-young age of 56. The number of people who remember her well is thus very few. Thankfully, Carey Mulligan’s firecracker portrayal of her in the film Maestro encompasses Felicia’s ardor, pain, poise, and everything in between. It is uncomfortable and often gut-wrenching to watch the scenes where Felicia acutely resents the life she wound up living, yet also a joyous experience to see the moments when she embraces the delights of being alive, loving her family, and caring deeply for others.

How best to reckon with such contradictory thoughts? Perhaps, given the confusing nature of mid-century America, we can simply be grateful for this honest look at a complex, gifted woman navigating the crosswinds of her era. Felicia’s enigmatic persona remains a graceful nod to the nuances of lived experience.

(Author note: my colleagues Heather Wallace, Jacob Slattery, and I have been researching Felicia Montealegre for the past year and a half, and it has been a career highlight to do so.)

Hannah Webster is Head of Licensing for The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc., and has helped manage Leonard Bernstein’s intellectual property for over seven years. She and her wife live in Brooklyn.

Sources:

Burton, Humphrey. Leonard Bernstein. (London and Boston: Faber and Faber, 1995), p. 298.

New York Post. November 30, 1962.

Simeone, Nigel. The Leonard Bernstein Letters. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013), p. 294.

The San Francisco Examiner. January 10, 1965.