Latest News

Reflections on Bernstein’s 1956 “Messiah”

Posted December 14, 2022

Reflections on Bernstein’s 1956 “Messiah”

By Mark Risinger

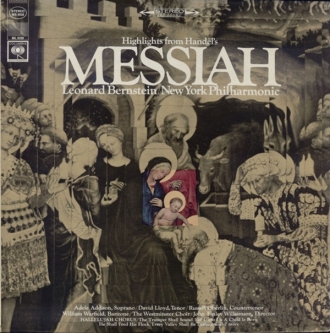

In his review of Leonard Bernstein’s 1956 performance of “Messiah” for the New York Times, Harold Schonberg wrote, “In short, a present-day 'Messiah' depends upon the taste of the conductor and his singers. And taste is often a subjective matter.” This observation lies at the heart of what made the performance controversial at the time, because it was so thoroughly a product of the conductor’s taste. The version that Bernstein presented with the New York Philharmonic – a pastiche of his favorite numbers with an expanded orchestration and in an order of his own choosing – had excitement and drama and his individual stamp on it throughout. The mistake that Bernstein and many others have made – including a commentator just last week on Interlochen Public Radio – is trying to explain and justify their choices in terms of a Handelian precedent, rather than personal taste, when it is unnecessary to do so.

Leonard Bernstein's score to Handel's "Messiah," courtesy of the New York Philharmonic Shelby White & Leon Levy Digital Archives. Peruse the score here.

To understand what I mean, it’s essential to recognize that we have inherited two separate and largely unrelated strands of “Messiah” performance tradition. The first - let’s call it Strand A - comprises the performances Handel himself gave between the Dublin premiere in April 1742 and his death in 1759. The second - Strand B - has its origins in the 1784 Commemoration of Handel held in Westminster Abbey, 25 years after the composer’s death. As a result of this Commemoration and the subsequent Handel festivals it spawned, the music of “Messiah” came to be excerpted, expanded, and celebrated in an altogether different cultural context and for vastly different purposes (mostly related to British nationalism) than in Handel’s lifetime. The endless array of different “versions” - abridgements, reorchestrations, transpositions - has created this separate tradition of “highlight” performances in churches, community choirs, and football stadiums all over the world. Bernstein’s Carnegie Hall performance was situated firmly in the tradition of Strand B and had nothing to do with Strand A (his liner notes for the LP notwithstanding). There is no harm in excerpting and enjoying the music in this way, but one need not and should not pretend that such a performance somehow represents a continuation of the tradition initiated by Handel himself.

The argument that Bernstein and many others have mistakenly tried to make runs as follows: since Handel himself performed several different versions of “Messiah,” no version of the work is truly “authentic” (a seriously problematic word that should be avoided altogether), so anything goes. While it is true that Handel made adjustments to some arias after the premiere and during the first few London seasons in which he performed the work, the fact is that by 1750 “Messiah” had achieved a relatively fixed state. Such adjustments as Handel made after that point had almost exclusively to do with accommodating individual singers - choosing either the alto or soprano version of a couple of arias - not with revising the structure and reordering the movements or altering the orchestration. In his will, Handel bequeathed a full score and a complete set of parts to the Foundling Hospital, where “Messiah” had achieved its greatest success in London, with the wish that it continue to be performed there for charitable purposes in perpetuity. Anyone wishing to understand and identify Handel’s authoritative version of the work need look no further than these sources. The work of Handel scholars and conductors of historical instrument ensembles over the last 40 years or so has been to pick up the threads of Strand A and bring us as close as we’re likely to get to the form and the sound of “Messiah” as Handel experienced it.

What can we say, then, about the virtues of the performance that the Philharmonic audience experienced sitting in Carnegie Hall in December of 1956? Bernstein was unquestionably a fan of Handel’s music, and his version sought to highlight some of the dramatic qualities in it that he most admired; by doing so, he demonstrated that truly great and timeless music can make its impact in multiple modes of presentation. Listening to the Columbia Records recording now, we are still struck by the incredible intensity of the orchestral playing and of the singing, from soloists and chorus alike. One can argue with tempi in almost any “Messiah” performance, depending on individual preference, but no one is going to dispute the impact of William Warfield’s impressive coloratura at top speed as he asked, “Why do the nations rage so furiously together?” In an era when U.S. / Soviet relations were rapidly deteriorating and international tensions were rising at an exponential rate, Warfield’s presence on the stage was significant for another reason, since he and soprano Adele Addison were African-American singers performing in a venue that still had segregated dressing rooms. Bernstein may well have been making his own sort of statement as a Jewish conductor, performing an explicitly Christian work, by including African-American artists seven years before the Civil Rights Act. Furthermore, almost no one at that time had heard a countertenor performing the alto solos until Russell Oberlin took the stage, delivering beautiful vocalism and initiating a performance trend that has become commonplace in the present day. The Westminster Choir, a chorus of 150 singers, manage most of the complicated contrapuntal sections with clarity, even if the sound is occasionally a bit raw, particularly in the tenor section. More importantly, however, this chorus delivers the words as if they really mean something, singing as if their lives depended on it. Too many “Messiah” performances of the historically accurate sort deliver polished choral sound without ever approaching the kind of meaning that Bernstein drew out of his performers.

When Haydn attended the Commemoration of Handel at Westminster Abbey in 1790, he was deeply inspired by the performances he heard of “Israel in Egypt” and “Messiah.” The story goes that he turned to his companion at the conclusion, burst into tears, and exclaimed “He is the master of us all!” Under the spell of Handel’s music, in what was certainly an oversized and extravagant production, he returned to Vienna to compose “The Creation.” Who knows what budding genius may have been sitting in Carnegie Hall 66 years ago and taken inspiration from another dramatic and powerful presentation of Handel’s music? Throughout his career, Leonard Bernstein made an impact on generations of young musicians, and it seems likely that by bringing Handel to Carnegie Hall and the recording studio, he once again helped foster a process of discovery and admiration by a new audience.

Mark Risinger holds a Ph.D. in musicology from Harvard University and is the editor of the critical edition of Handel’s Semele for the Hallische Händel-Ausgabe (Bärenreiter Verlag, 2022). A member of the Board of Directors of the American Handel Society and a Trustee of the Handel House Foundation of America, he lives in New York City.