Latest News

From the Archives: Hans Weber (1930-2020): A Personal Appreciation

Posted November 20, 2020

Hans Weber (1930-2020): A Personal Appreciation

by Charlie Harmon

(as printed in the 2020 Spring/Summer issue of Prelude, Fugue & Riffs)

Charlie Harmon was Leonard Bernstein’s assistant from 1982 through 1985. His memoir of those years, On the Road and Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein, was published by Charlesbridge, an imprint of Imagine Books, in 2018. His close association with Leonard Bernstein’s longtime colleague and friend, Hans Weber, who died on March 7, 2020, moved Mr. Harmon to share the following remembrance.

Leonard Bernstein’s long-time colleague and friend Hans Weber died at his home in Hildesheim, Germany, on March 7, 2020, two months shy of his ninety-first birthday. As a condolence to his wife Klara, their daughter Antje and son Jan, I offer this brief reflection on one of Leonard Bernstein’s most highly respected colleagues.

From 1976 to 1990, Hans Weber was the recording producer for Leonard Bernstein’s Deutsche Grammophon recordings, which now number nearly two hundred titles. As chief of the recording crew, Mr. Weber was responsible for every aspect of the finished product, whether it was an all-American album with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the ballets of Stravinsky with the Israel Philharmonic, or another American album featuring the music of Charles Ives with the New York Philharmonic. Among the many collaborations between Mr. Weber and Leonard Bernstein, the most monumental were the complete orchestral works of Beethoven, Brahms, Schumann, and Mahler.

Shortly after Leonard Bernstein’s death, Mr. Weber recollected, “It was not easy for me to be the occasional critical counterpoint among the chorus of enthusiasts, yet I believe that LB appreciated having me as his objective ear in the control room.” In fact, Mr. Bernstein often claimed that Hans Weber possessed “the best ears in the business.” Equally valuable were his musical memory and discretion. Decades after the fact, he could recall individual performances with precision, including finer points and pitfalls (“there were problems,” was the most caustic phrase Mr. Weber would ever say), and even the timings of individual movements.

Leonard Bernstein retained final approval of all his DGG recordings, via listening sessions usually shoehorned into concert weeks abroad. During the months when he and Stephen Wadsworth wrote A Quiet Place, there was no time to travel, so Hans Weber came to New York, schlepping the tapes of thirteen works and the boxy playback console.

As I drove us to Connecticut, Mr. Weber commented on the reckless truck drivers on the interstate, so for contrast I detoured through sedate Greenfield Hill with its landmark church on the green. He admired the bucolic charm but chuckled at the founding date of seventeen-hundred-and-something. A couple years later, Mr. Weber took me to his local church in Hildesheim: the mammoth cathedral, one of Germany’s most historic, completed in 1020. Ach ja, jetzt ich verstehe.

On that January afternoon in 1983 in Connecticut, LB put his opera manuscript aside and plunged right in to the listening session. After three hours he suggested a pause for dinner, but he wasn’t in a good mood. The mental shift from conductor to composer was a perennial hurdle for LB. For four months he had been a diligent composer; it was distracting to hear works by Copland and Gershwin and Brahms when what he most needed in his head was the music of Bernstein.

In a fit of temper, LB cut the dinner short, and nudged Hans Weber back to the listening session, with nine or ten works to go. The studio took on the atmosphere of a college all-nighter before a critical exam. Around one in the morning, they’d reached the fourth symphony of Johannes Brahms, one of the two works in which Brahms wrote for a triangle. The triangle sounded especially insistent. In fact, it kept on going, throughout the third movement, like an unstoppable wind-up toy. “I spliced this myself!” Mr. Weber shouted, as he stopped the tape.

And the ringing continued! It was the telephone on LB’s desk. LB’s sister Shirley had a question about that week’s crossword puzzle in The Guardian, a perfectly legitimate phone call for LB at that late hour. It certainly changed the mood that night, and when Mr. Weber returned to the Deutsche Grammophon offices and told this story, he got a resounding guffaw from his colleagues.

The Bernstein legacy owes a great debt to Hans Weber, whose career blazed atop the heights of serious music in the 20th century. Everyone who knew him will always cherish his high standards and his collegial friendship.

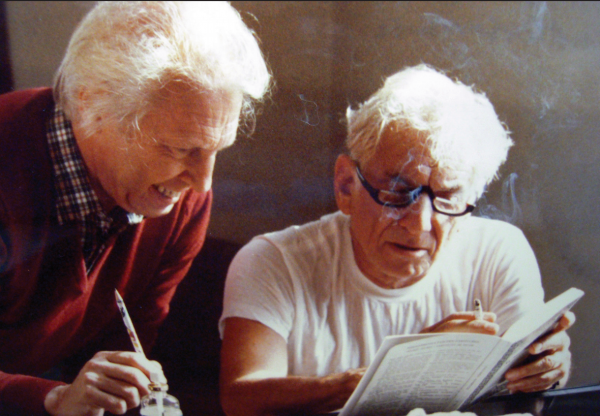

[Photo: Hans Weber and Leonard Bernstein review a score. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.]