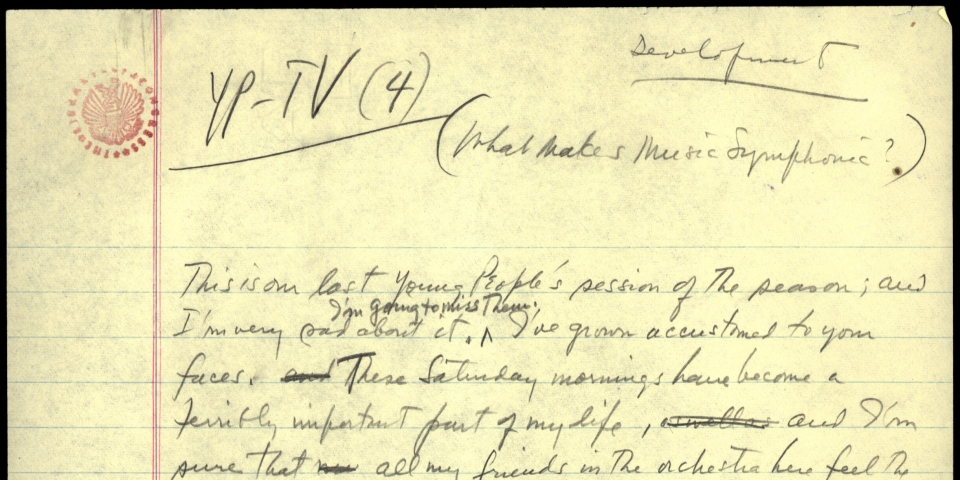

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsWhat Makes Music Symphonic?

Young People's Concert

What Makes Music Symphonic?

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 13 December 1958

I am very, very happy to be back again with you. These Young People's Concerts have become a terribly important part of my life, and I am sure that all my friends here in the orchestra agree with me. We hope you do too. I've received so many letters from you in the television audience expressing disappointment because our final program of last year was not televised due to technical difficulties I won't go into, that I have been persuaded to repeat it and so we are going to open this year's series by again discussing the subject — what makes music symphonic?

It's sort of a hard subject, so I guess it might be worthwhile even for those of you in Carnegie Hall here who did hear it discussed last spring to hear it discussed again. But really the only reason it is such a hard subject at all is that it is always talked about as a hard subject, people make it sound like dry book-stuff, and they use a lot of long, hard words. But actually, it's not so hard, and if you want to know the truth, it's the most exciting part of all music. The key to it is development, which is sort of a hard word.

But really not so hard; you all know the word development — like when your doctor is giving you a physical check-up and he says, "You're developing fine muscles and you're developing good teeth and hair. Or your teacher in school might say to you. "Your mind is developing very nicely."

You see, development is really the main thing in life, just as it is in music; because development means change, growing, blossoming out; and these things are life itself.

But what does development mean in music? The same thing as it means in life; great pieces of music have a lifetime of their own from the beginning to the end of any piece; and in that period all the themes and melodies and musical ideas the composer had, no matter how small they are, grow and develop into full-grown works, just as babies grow into big, grown-up people.

Now first of all, let's listen to one of the greatest examples of development in the whole history of music: the last movement of Mozart's "Jupiter" Symphony. Now this movement grows in all kinds of different ways from the first four notes that you hear right at the beginning. They go like this.

[PLAY: Mozart - Jupiter Symphony]

Four very simple notes. Now see if you can follow the fascinating life that blossoms out of these four notes as the piece develops.

[ORCH: Mozart - Jupiter Symphony, Finale]

Now that is what you call development. Those first four notes we heard

[PLAY: Mozart - Jupiter Symphony]

have grown into a big mighty work. Now how does this happen? How does that development actually work? Well it happens in three main stages, kind of like a three-stage rocket going into space. First stage is the simple birth of the idea, the flower growing out of a seed. You all know that seed that Beethoven plants at the beginning of his Fifth Symphony — again four little notes

[PLAY: Beethoven - Fifth Symphony]

That's the theme, and out of it arises a flower, which goes like this:

[PLAY: Beethoven - Fifth Symphony]

Then the second stage is the growth of that flower; it just gets bigger and bigger and bigger until it's like this:

[PLAY: Beethoven - Fifth Symphony]

The same thing happens with almost any piece you can think of. Take the Fifth Symphony of Sibelius, another great composer, from Finland. His Fifth Symphony begins again with a four note seed, that goes like this:

[PLAY: Sibelius - Fifth Symphony]

Then out of this seed arises a big, shining flower.

[PLAY: Sibelius - Fifth Symphony]

Then comes the second stage when the flower gets bigger and grows to something like this:

[PLAY: Sibelius - Fifth Symphony]

Then comes the third stage - which is the most important one: change, the stage of change. The flower actually changes its appearance. Or perhaps it's more like a fruit tree, which we first see all bare in winter; then in the spring, covered with blossoms, looking like a completely different tree; and then, in summer, the blossoms fall away, and fruit begins to grow. Again it looks like a different tree. So, the same tree has had three different looks in three different seasons; but it's still the same tree. The same thing happens to us; we change from year to year, in our character, in our likes and dislikes, even in the way we look. For instance, I was born blond. Would you believe that? And I was blond until I was ten years old. And ten years from now I'll probably be all gray or maybe have no hair at all. The same thing happens in music. Let's take Tchaikovsky's Fourth Symphony, for instance, and see how this third stage of change works. In the last movement of his symphony, Tchaikovsky uses an old Russian folk-song.

[PLAY: Little Birch Tree]

I guess you all know that little tune. Now this theme, or melody, or tune, or whatever you want to call it goes through all kinds of changes before Tchaikovsky is done with it. It is played softly,

[PLAY: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

it's played loudly,

[PLAY: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

and it's played in different keys,

[PLAY: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

and it's played by different instruments. Like the oboe:

[OBOE: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

or like the trombone:

[TROMBONE: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

And you will hear it suddenly twice as slow

[SING: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

and then you will hear it twice as fast.

[SING: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

But it's always changing and it always sounds different. Now let's listen to a development section from this symphony of Tchaikovsky and this section develops that tune only - nothing else - and see if you can follow all the changes that happen.

[ORCH Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

Now did you follow those changes? You see how that little tune has been tossed around — how its shape has actually been changed? But all that is part of the growing-up of this piece, the sort of life-story of the symphony.

Now all music isn't symphonic, of course; but all music does develop in some way or another, even little folk songs, or a simple rock'n'roll tune. But these little songs develop mainly by repeating, by repetition. That's the easiest, most babyish way to develop anything - by just saying it over and over again. It's like an argument; if you're a real brainy type, you'll develop your argument with variations and with changes. Let's say you wanted to prove, for example, that Canada is a tropical country. Well, that's a hard one. You would try to prove that somebody found tropical flowers growing in Saskatchewan, let's say. Or then you would argue that on a certain day last winter the sun was hotter in the Canadian Rockies than it was in Miami Beach, etc., etc., whatever. You'd find arguments. But if you're more babyish and simple-minded, you would just say it over and over again: Canada is a tropical country, Canada is a tropical country, Canada is a tropical country, until you had just convinced the person you're arguing with by beating him over the head. That's what popular songs do; they develop by beating you over the head with their argument. Take that Marching Song from the picture The Bridge over River Kwai, for example. I think you all know that one, and you can whistle along if you want even. Now watch how this one develops.

[PLAY: Alford - Colonel Bogey March]

Now it goes all over again. You understand what I mean by baby development. It's developing, but just by repeating. It could go on endlessly that way. But, as we said, repetition is just a baby way of developing. The first step toward real developing is in the idea of variation. Now all variation is another kind of repetition, only it's not exact repetition. Something has to get changed. And that's what makes jazz so exciting; when a jazz player gets hold of a popular song, he just doesn't play it over and over again the way it was written; he makes his own variations on it. For example, let's take that same Marching song and let's play it with a variation with some of the boys in the orchestra. And I think you'll see what I mean.

[INSTR: Alford - Colonel Bogey March]

Now that is beginning to be development. It's development because it's changing. It's not the same tune we began with. But it's not exactly symphonic yet. I guess none of you would claim that was symphonic. But now let's make a big jump and see how Beethoven uses the same idea in his Eroica Symphony - the same idea, but oh, what a difference. In the last movement of his Eroica Symphony, Beethoven writes a series of variations on a theme that's so skinny and small, it's not even a real theme; it's not even a tune. It goes like this.

[ORCH: Beethoven - Eroica Symphony]

That's the theme. Now listen to how he makes a variation on it.

[ORCH: Beethoven - Eroica Symphony]

That's one variation. Now listen to this. Here's another.

[ORCH: Beethoven - Eroica Symphony]

That's another. And here's another.

[ORCH: Beethoven - Eroica Symphony]

You see how the original skinny notes are always there,

[SING: Beethoven - Eroica Symphony]

no matter what other stuff is going on. Now listen to this next variation; and see if you can hear those skinny notes down in the basses and cellos.

[ORCH: Beethoven - Eroica Symphony]

Now on top of that a whole new melody is being played by the oboe.

[OBOE: Beethoven - Eroica Symphony]

Now listen to it all together: the skinny notes in the bass and the new melody on top.

[ORCH: Beethoven - Eroica Symphony]

You see what a long way we've come from those first little skinny notes.

Well that's variation. Now what have we learned so far? We've learned that the basis of all development is repetition, but the less exact the repetition is, the more symphonic it is. We've also learned that all music to some degree or other depends on development, and the more it develops, again, the more symphonic it is. So now what we have to find out is - how do composers use this not-exact repetition to develop their themes into big symphonic pieces?

Well, the first way we've already seen - variation. But there are different ways of making variations and one of the most common is — now watch out for this hard word! — sequences. (You can see it on the machine.)

Don't let the word scare you; it's a very simple trick, really. All a sequence does is to repeat any series of notes at a different pitch. That's all. For instance, I could make sequences out of almost anything - like you remember a number Elvis Presley used to sing called "All Shook Up". Well, let's take a phrase from that.

[SING: Blackwell & Presley - All Shook Up]

Now we'll make a sequence out of it.

[SING: Blackwell & Presley - All Shook Up]

And so on. That's a sequence. It's easy and you can see right away how useful this is in building music; because it's a way of developing, of piling up bricks, higher and higher.

[SING: Blackwell & Presley - All Shook Up]

and that gives the impression of getting somewhere, in other words. of development. Of course, a sequence can also repeat at lower pitches — I could sing:

[SING: Blackwell & Presley - All Shook Up]

but that's not very widely used, because it's not half so exciting, and it doesn't mount up all the time, like a building. Let's listen to some examples of sequences in symphonic music. Here's one of the most famous examples in the history of music — from Tchaikovsky's "Romeo and Juliet"; and listen to how this love-music builds up in sequences.

[ORCH: Tchaikovsky - Romeo and Juliet]

Did you hear those sequences, piling up power 'til the music explodes on the famous love theme?

[SING: Tchaikovsky - Romeo and Juliet]

Up and up. As you see, sequences are a very easy way to develop music; it's a form of climbing repetition that's almost guaranteed to sound exciting. Look what Gershwin did in the "Rhapsody in Blue", where he takes a theme that goes:

[PLAY: Gershwin - Rhapsody in Blue]

and he makes a sequence out of that that's tremendously exciting.

[PLAY: Gershwin - Rhapsody in Blue]

I guess you find that exciting; I do. But sequences don't always have to be passionate and exciting. Take the "Jupiter" Symphony, for instance, that we heard before, where Mozart is developing the theme that goes,

[PLAY: Mozart - Jupiter Symphony]

as well as those first four notes.

[PLAY: Mozart - Jupiter Symphony]

Now listen to the sequence he makes out of these two themes.

[ORCH: Mozart - Jupiter Symphony]

That's an unpassionate sequence.

But there's still a much more important way in which repetition works for development, and that is something called imitation - the imitation of one orchestra voice by another. Now why is this different from any other kind of repetition - just because something is played on the oboe and then imitated by the clarinet and then imitated by the strings? No, it's much more than that. The exciting thing about imitation is that when the second voice comes in, imitating the first, the first one meanwhile goes on doing something else, so that suddenly there are two melodies going on at the same time. That's the great secret of music called counterpoint — more than one melody at a time. It's really not such a secret; you've all done counterpoint yourselves — like every time you sing a round, "Row, Row, Row Your Boat", "Three Blind Mice", "Frere Jacques". I'd like you to think of these rounds keeping imitation in mind, so that you can see how symphonic music develops in the same way. I'd like to have a try at "Frere Jacques" with you, right now. We'll do it in two-part imitation, we'll start with everybody upstairs singing,

[SING: Frere Jacques]

and then everybody downstairs coming in on the imitation while the upstairs people go on to the next phrase. OK? Go.

[AUDIENCE: Frere Jacques]

Beautiful. ... You mustn't go on. You leave them singing "ding, dang, dong" all by themselves. You understand? All right. That's was good for a first try. But that was only two parts; let's get more complicated. Let's do it in three parts. Who's going to do the third part? The orchestra will. We'll start with everybody upstairs, then everybody downstairs comes in for the second imitation. Then the men in the orchestra come in for the third imitation. OK. Let's try that. Ready? Go.

[AUDIENCE: Frere Jacques]

Wonderful. I'd like to go on for a long time with that because you sing it so well. But I want to get really complicated now, really symphonic, and try it in four parts; now how are we going to do that? You start upstairs, then you downstairs, then the orchestra, and then the fourth imitation will be by all the parents and teachers, and well - all the grown-ups in the audience. I hope you grown-ups are as good as your kids. All ready? Good?

[AUDIENCE: Frere Jacques]

Real loud! Louder! Good! Great! Louder! You're wonderful. You're all hired.

But now you see how complicated imitation can get, and how rich the sound can get as the music develops in this way. What you've just been singing is, in fancy musical language, a canon. That's not the military type of cannon: it has only two n's, instead of three. And if it gets even more complicated, it becomes a fugue, but let's not go into that now. All you have to know is that music that develops through canons and fugues can develop the greatest changes of all that can happen to musical themes. For instance, a tune can turn up twice as slow, or twice as fast, as we heard in the Tchaikovsky. And it can turn up backwards or upside-down. Can you imagine "Frere Jacques" backwards. Have you ever thought of it? It goes like this.

[SING: Frere Jacques]

It sounds pretty. But it's a different tune. But that's a development of the first "Frere Jacques". And upside down, it's even prettier. It goes:

[SING: Frere Jacques]

Sounds pretty, didn't it? These are all ways of using imitation and using counterpoint to change the shape of music so as to give it new life all the time.

Now all these ways we've been talking about of developing are ways of building up — developing themes by adding to them, adding voices, adding sequences, adding variation, decoration, imitation. But there is also a way of developing that builds up by breaking down — now doesn't that sound very peculiar? But it's true, and a very good method it is, too. It was a great favorite of Beethoven and Tchaikovsky. In that final movement of Tchaikovsky's Fourth Symphony we heard before, there's one place where Tchaikovsky is developing this theme:

[PLAY: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

Now, as usual, he treats it first in sequences, like this:

[ORCH: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

But now, instead of adding to that, he builds excitement by breaking it in half, and suddenly using only the second half of it. Like this:

[ORCH: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

You see. Then he breaks that in half and develops only that half,

[ORCH: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

and now we're down to four notes only,

[SING: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

which he's developing in sequences.

[SING: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

But now it divides again, like an amoeba, and the sequence builds on only the last two notes.

[SING: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

Just that. Listen.

[ORCH: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

Now it's broken down to such tiny fragments and bits that it's just dust, ashes, little pieces of whirling scales.

[ORCH: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

That is development by breaking down. Now listen to this whole passage together, and see what excitement and fury Tchaikovsky can build up by breaking down. This is, strange as it sounds, making music grow by destroying it.

[ORCH: Tchaikovsky - Fourth Symphony]

Well, I think now we've seen enough ways in which music can grow and change and blossom so that we're now ready to take a good look at one movement of a symphony, and see how it develops. Then, when we finally play you the whole movement, I think you'll be able to hear this movement in a brand new way — at least I hope so — not just hearing a bunch of tunes, or exciting sounds made by a big orchestra, but as a whole process of growing, which is the most important thing to be able to hear in any piece of music.

Now the piece we're going to put under our microscope is the last movement of Brahms' Second Symphony; brilliant, joyful, satisfying music. But what makes it so satisfying is not just that it has pretty tunes and nice sounds; it's the way it develops. Now it starts right off with the main theme.

[ORCH: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

That's the main theme. Now there are certain elements in that softly-whispered melody that are going to come in for a lot of changes: first of all the opening figure -

[PLAY: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

Then this phrase, which you've just heard, made up of descending fourths, as they're called, intervals of the fourth.

[PLAY: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

But then, a few bars later on, these same fourths

[PLAY: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

are used again, in a whole other rhythm.

[ORCH: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

You see how it's already begun to develop, even while the melody is still being played for the first time, while they're developing it. Those same fourths

[PLAY: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

which we heard first, have now turned into:

[PLAY: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

and that's already a big change, that's a growth, a development. Now comes another development — a change of orchestra color. That tune which the strings have just played is now repeated by the woodwinds. Which makes a change of color.

[ORCH: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

You see what I mean by a change of color? Now, the next change is one of loudness. Listen to the melody as it comes now.

[ORCH: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

Some difference, huh? a simple change, from whispering to shouting - but that's also development. Now, after a few more bars, we run into something called — another hard word, watch out — augmentation, which is only a long hard word for our old friend twice-as-slow. All it means is that you take the notes of your melody and spread them out thinner, so that they take up more room and more time; and that's also a good way of developing a theme. That's what Brahms does here: he takes those fourths that we just heard

[PLAY: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

and he spreads them out this way.

[ORCH: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

You see how this bigger way of saying the same thing actually changes the shape of the tune? Instead of

[PLAY: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

we now have:

[PLAY: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

A real rhythmic change. We're really forging ahead now. Now at this very point, Brahms pulls out the old stand-by sequences. And the sequences are built on that very last figure we just heard the violins play.

[PLAY: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

Here it goes, building up its power like the Elvis Presley tune.

[ORCH: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

You see there's no end to the tricks Brahms has for making his music grow; he's got millions of them. For instance, at this point where we just left off, he takes the notes of that sequence we just heard

[PLAY: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

and turns them into an accompaniment

[PLAY: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

which is playing under a new, sweet melody, in the clarinet, which is itself a development of those fourths we heard before. Only now it's twice as slow. Whenever I hear this passage, I am always filled with wonder and respect for the way Brahms makes everything in his music out of something else in his music: - it's all part of one great thought, and every single part is a branch of the same great tree. Listen to this section.

[ORCH: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

Isn't that amazing? That's first-class development. Now Brahms is ready to give us his second theme, which is a rich, broad, beautiful melody, that goes like this.

[ORCH: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

But even here, in this brand-new melody, Brahms has to work in a development of something earlier: he takes the opening notes of the movement

[PLAY: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

and makes an accompaniment figure out of them to accompany this new melody, and that connects the new melody to what we've heard before, it's like connecting a new branch to the tree. See if you can hear it. Here's the accompaniment.

[ORCH: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

You see how that sounds exactly like the beginning of the symphony. Now listen to the melody again, with one ear, and if you can, with the other ear listen to the accompaniment which is made out of that earlier material. And see if you can hear both things at once.

[ORCH: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

Isn't that wonderful? Did you hear both things? No? Yes? Good. Now this new melody we just heard comes in for a change; this time it changes from what we called the major, to what we call the minor. I won't bother explaining that to you, but it sounds like this:

[ORCH: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

almost sounds like a whole different theme in the minor, doesn't it?

Well that's a lot of development so far, but believe it or not Brahms hasn't yet even reached what is usually called the development section of a movement! Can you imagine that? He's only begun telling us his themes. He still has in front of him the main job of developing them. But his mind was so full of musical ideas and so rich that he couldn't even write down his simple melodies without developing them at the same time. That's why in this short first part of the movement he has already developed more than most composers do in a whole symphony — and it's only the beginning.

If we had time, I'd love to go through the rest of this amazing movement, and show you all the other marvelous ways in which he grows his music, like a master gardener. The way he uses variation, and puts two and three melodies together at a time in counterpoint; the way he uses that breaking-up system we talked about before; the way he takes little scraps of melodies and develops them by themselves; or the way he turns themes upside-down like pancakes.

But the remarkable thing is not just that a melody is upside-down like a pancake; it's the fact that it's upside down, and it sounds wonderful upside-down. You see, anyone can take a tune and turn it upside-down, or play it backwards, or twice as fast, or twice as slow — but the question is — will it be beautiful? That's what makes Brahms so great; because with him music doesn't just change, it changes beautifully. The trick is not just to use all these different ways of developing music, but to use them when it's right to use them, at the moment so that the music always makes sense as musical expression, as feeling, as emotion. That's hard to do and that's what Brahms could do like nobody's business.

So now that you have some idea of what makes music symphonic - and the answer, as you know very well by now, is development - we're going to play this whole movement for you, straight through: and I'm hoping that you'll be able to hear it with new ears now; That you'll be able to hear the symphonic wonders of it, the growth of it, the miracle of life that runs like blood through its veins and connects every note to every other note, and makes it the great piece of music that it is.

[ORCH: Brahms - Symphony no. 2]

END

© 1958, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.