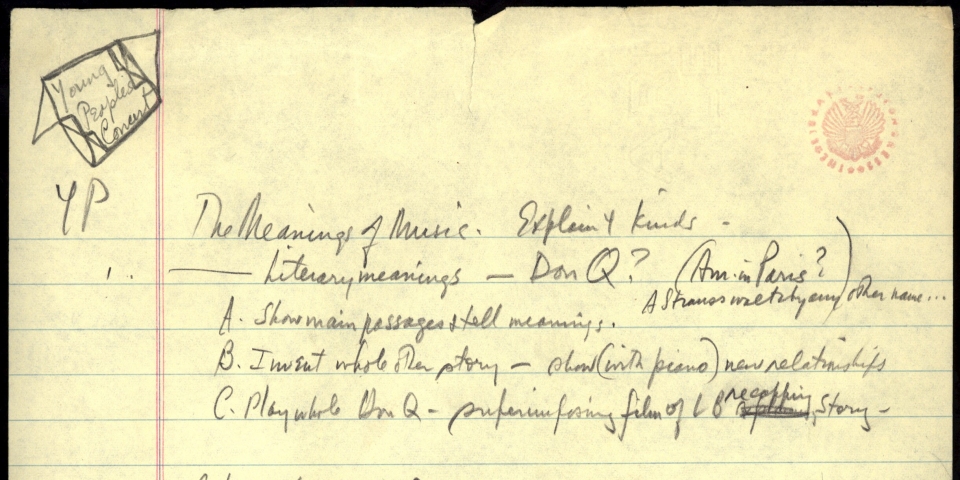

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsWhat Does Music Mean?

Young People's Concert

What Does Music Mean?

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 18 January 1958

[ORCH: Rossini - Overture to William Tell]

O.K. Now, what do you think that music is all about? Can you tell me?

[KIDS ANSWER]

That's just what I thought you'd say: cowboys, bandits, horses, the wild west. I know my little daughter Jamie, who's five years old, who's sitting up there, agrees with you. When she heard me play this piece, she said - "That's the Lone Ranger song, Hi-ho Silver!" Well, I hate to disappoint her, and you too, but it isn't about the Lone Ranger at all. It's about notes—-E-flats and F-sharps. You see, no matter how many time people tell you stories about what music means, forget them. Stories are not what the music means at all. Music is never about anything. Music just is. Music is notes, beautiful notes and sounds put together in such a way that we get pleasure out of listening to them, and that's all there is to it.

You see, no matter how many time people tell you stories about what music means, forget them. Stories are not what the music means at all. Music is never about anything. Music just is. Music is notes, beautiful notes and sounds put together in such a way that we get pleasure out of listening to them, and that's all there is to it.

When we ask "what does it mean - what does this piece of music mean?", then we're asking a very hard question. And that's the question we're going to try to answer today.

Now, It's a funny thing about this meaning business - in music, anyway. When you say "What does it mean?", what you're really saying is "What is it trying to tell me?", or "What ideas does it make me have?" Just like words; when you hear words, you get ideas from them. If I say to you "Ow, I burned my finger!", then immediately you get an idea from what I said or some ideas. You get the idea that I burned my finger, that it hurts, that I might not be able to play the piano any more, or that I have a loud ugly voice when I scream, lots of different ideas like that. That's words. But if I play notes, some notes on the piano, like this

[PLAY]

the notes don't tell you any ideas; these notes aren't about burning your finger, or sputniks, or lampshades, or rockets, or anything.

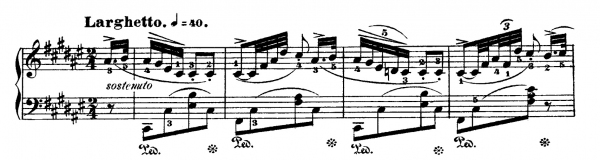

Well, what ARE they about? They're about music. For instance, take this piece by Chopin:

[PLAY: Chopin - Nocturne Op. 15 No. 2 in F-Sharp Major]

Beautiful, isn't it? But what's it about? Nothing. Or take this Beethoven Sonata:

[PLAY: Beethoven - Piano Sonata No. 21 in C major, Op. 53 "Waldstein", Opening]

That's not about anything, either. Or take this piece of boogie-woogie:

[PLAY: Boogie Woogie]

It's not about anything either. None of them are about anything, but they're all fun to listen to. Why should they be fun to listen to? I don't know; it's a part of human nature to like to listen to music. You see, notes aren't like words at all. Because if I say one single word all by itself to you, like "rocket", immediately you have an idea; you see a picture in your mind. Rocket! Bang! Picture!

But if I play a note, one note all alone—

[PLAY]

—means nothing. It's just a plain old F sharp of a B flat.

[PLAY]

A sound, that's all, higher or lower, louder or softer—a sound that can seem very different if I play it

[PLAY]

or if I sing it,

[SING]

or if an oboe plays it,

[OBOE]

of if a xylophone plays it,

[XYLOPHONE]

of if a trombone plays it,

[TROMBONE]

Very different. It's all the same note—only with a different sound. Now all music is a combination of sounds like that one.

[PLAY]

or that [PLAY], or that one [PLAY], or that one [PLAY] put together according to a plan. The guy who plans it is called the composer—whether he's called Richard Rodgers or Rimsky-Korsakov—he's the composer, and his plan is to put the sounds together with rhythms and different instruments or voices or whatever in such a way that what finally comes out is exciting, or fun, or touching, or interesting, or all of those together. That's called music and it has a musical meaning, which has nothing to do with any stories or pictures or anything like that. Of course if there is a story connected to the music, okay; sometimes it's good in a way, it gives an extra meaning to the music; but it's extra—remember that. And so, whatever the music really means, it's not the story. So what does it mean? That's what we're going to find out.

Now let's take the first step. Remember the piece we played at the beginning?

[SING: Rossini - Overture to William Tell]

That wild west piece of music? Well, for one thing it can't mean the Wild West, for the simple reason that it was written by a fellow who never heard of the Wild West—an Italian named Rossini. We think his music means horses and cowboys and the Wild West because we've been told so by the movies and television shows. But Rossini really wrote this piece as an overture to an opera called "William Tell," which is about people in Switzerland, which is pretty far from the Wild West. Well, then, maybe the music is supposed to be about William Tell and Switzerland, instead of about cowboys. Is that what it's about?

[KIDS RESPOND]

No! It's not about William Tell or cowboys or lampshades or rockets or anything. Then what makes it so exciting? Well, there are a million reasons: but they're all musical reasons. That's the main point. For instance, take the rhythm—

[SING]

—which is like the rhythm of galloping horses

[PERCUSSION: CHINESE BLOCKS]

—or like the rhythm of drums in a battle

[SNARE DRUMS]

but that doesn't mean that the music is about drums or horses or battles; the meaning is only the excitement of that rhythm. Another reason it's exciting is that it has a mighty tune, one that's easy to remember and stirs your blood: it starts with a phrase going up—

[SING: Rossini - Overture to William Tell]

—and answers itself with a phrase going down.

[SING: Rossini - Overture to William Tell]

It's like a question and answer. Or maybe it's more like an argument with the second person winning it. Let's try and have that argument now, you and me. And see who wins. I'll sing the first phrase—

[SING: Rossini - Overture to William Tell]

—and you'll argue back with the second phrase.

[SING: Rossini - Overture to William Tell]

Then I'll argue back with the third phrase—

[SING: Rossini - Overture to William Tell]

—and you'll wind it up with the fourth phrase.

[SING: Rossini - Overture to William Tell]

O.K.? Ready, go!

[SING WITH AUDIENCE: Rossini - Overture to William Tell]

You win! You see how exciting that last phrase is?

[SING: Rossini - Overture to William Tell]

It has all the excitement and triumph of winning an argument. It makes you feel good. But there's still more reasons why this music is exciting; for instance, the way it's played, the instruments that play it, like these trumpets at the beginning.

[ORCH: Rossini - Overture to William Tell]

Or the violins, who use their bows in a jumping way to make that galloping sound, takata, takata. Will you show us, Mr. Corigliano?

[CONCERT MASTER SHOWS]

You see, and when all the strings do it together, it really gallops!

[ORCH: Rossini - Overture to William Tell]

So you see, this music is exciting because it was written to be exciting, for musical reasons, and for no other reasons.

Well, if all that's true, then why does a composer put names on his music at all? Why doesn't he just write something called Symphony or Trio or Composition Number 900 and 50 and 12 or anything? Why does he give his music a name, like "The Sorcerer's Apprentice", or whatever it happens to be, if it's not important to the music? Well every once in a while an artist is stimulated to express himself by something outside himself—something he reads, or something he sees, or that happens to him. Haven't you ever felt that you wanted to dance or sing because something happened to you that made you want to dance or sing or express your feelings in some way? I'm sure you all had that feeling. Well, it's the same with a composer; for instance Johann Strauss wrote lots of waltzes, and one of them goes like this:

[PLAY: J. Strauss - The Blue Danube]

Do you know the name of that one?

[KIDS RESPOND: THE BLUE DANUBE]

Right! Now, maybe the Danube River inspired Strauss to write that waltz. I don't know, I have my doubts. But those notes don't have anything to do with the Danube River, do they?

[KIDS RESPOND]

Now what's this one?

[PLAY: J. Strauss - Tales from the Vienna Woods]

[KIDS RESPOND]

Right, Tales from the Vienna Woods. Well, why couldn't that be called by "The Blue Danube", of "The Emperor Waltz", "The Tennessee Waltz", or "The Missouri Waltz" for that matter. What's the difference? A Strauss waltz by any other name is still just a lovely waltz. The name doesn't matter, except to help you tell one waltz apart from the other, and maybe give the music a little more color, like a fancy dress costume.

Now I'm going to try a trick with you. We're going to play a piece that has a story, but a good story, but I'm going to tell you the wrong story. I'm just going to make one up out of my head that doesn't belong to this music at all. And I'm not going to tell you the real name of this piece; and you see if the story and the music don't go together just as well as if it were the real story. Okay, here goes.

In the middle of a big city there stands an enormous jail, full of prisoners. It's midnight and all the prisoners are asleep except for one who can't sleep because he was put in jail unjustly. He spends the whole night practicing on his kazoo while all the other prisoners are sleeping and snoring all around him. You all know what a kazoo is? Well, this kazoo-playing prisoner has a friend who is going to come and rescue him tonight and this friend's name is Superman! So Superman comes charging down through the alley on his motorcycle.

[ORCH: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

Then he whistles his secret whistle so his friend the prisoner will know he's coming.

[ORCH: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

As he gets near the prison, he hears all the prisoners snoring away peacefully in the dead silence of the night.

[ORCH: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

And over this snoring he hears his friend playing on his kazoo, which gets louder and louder as gets nearer.

[ORCH: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

Suddenly, he charges into the prison yard and bops the guard over the head.

[ORCH: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

The kazoo stops playing, and with all the snoring still going on, he grabs his friend and whisks him away on his motorcycle!

[ORCH: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

The snoring gets farther, and farther away until we don't hear it at all anymore.

[ORCH: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

And our hero arrives at last to freedom!

[ORCH: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

That's the story. Now let's hear how this sounds all put together. And remember to keep this story in your mind. Here goes!

[ORCH: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

[Bernstein - voiceover]

Here comes Superman!

He hears the whistle.

There goes the snoring

There's the kazoo.

And now here comes Superman.

Bop!

He grabs his friend.

And they're off.

The snoring gets softer.

They're free!

[END OF ORCH]

Now all that makes good sense, doesn't it? Makes perfectly good sense, But it's not the real story at all. What this piece really is, is a part of a much longer piece by Richard Strauss called "Don Quixote"; and in it Strauss was trying to tell a whole other story in this music which is something like this: Don Quixote is the name of a silly old man, back in the days of knights and armor and horseback - a foolish old man who read too many books about knighthood and chivalry and conquering armies for his beautiful lady, and all that sort of nonsense, and who finally decided he was a marvelous knight himself. So off he goes on his skinny, bony old horse to conquer the world.

[PLAY: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

He has with him a companion named Sancho Panza, a little fat, jolly fellow, who is very faithful to his master, but is also sensible enough to know that his master is a little cuckoo. So we hear him laughing at old Don Quixote.

[PLAY: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

Suddenly, Don Quixote spies a flock of sheep in the middle of the field going baa-baa.

[PLAY: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

That's all that stuff that you heard before that we thought was snoring. And with them is a shepherd keeping the sheep, playing on his pipe, as all shepherds do.

[PLAY: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

Not a kazoo, but a shepherd's pipe. Don Quixote, in his mixed up mind thinks that the sheep are an army specially put there for him to conquer, so in he charges with his sword flashing.

[PLAY: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

And the sheep run off in all directions, baa-ing wildly. He is convinced he has done a truly knightly deed, and is he proud!

[PLAY: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

Now let's listen to it all over again, with the real story in mind. And see how it sounds.

[ORCH: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

[Bernstein - voiceover]

Sheep, you understand.

[END OF ORCH]

Now was that music any different from what we played before? Was it? Is it more exciting, or more fun, or better music? No. Does it have any different meaning? No. It's exactly the same, only the story is different.

In fact, there are a hundred other stories I could have made up out of my head for the same piece of music, but the music would still have been just as good or just as bad as it is without any story at all. Now, do you see what I mean? Well if you don't, I'm going to have to try again. I'll take another little bit of this Don Quixote piece by Strauss.

Later in that same piece there is a another part about another adventure the old fellow has; when he and his friend Sancho Panza take a wild ride through the air on a wooden horse. It goes like this:

[ORCH: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

In this part there is even a windmachine in the percussion section to give you the effect of the wind whistling by as they whoosh up and down through the clouds.

[ILLUSTRATE]

Now why couldn't this music be describing the flight of a jet plane? Or a satellite whistling around in its orbit, or maybe even some old giant snoring like the prisoners in the jail? Let's make believe it is about some old giant snoring and see how the music fits.

[ORCH: R. Strauss - Don Quixote]

Isn't that exciting music? No matter what it's about; it's still exciting because the music is exciting, and for no other reason.

Now that's enough talk about music that tells stories. Let's take a big step now towards finding out the answer to our first question "what does music mean" by listening to some music that doesn't try to tell a story, but only tries to paint a picture, in a general sort of way, or to describe an atmosphere. The look of something, the feel of something - a night in the woods, or an old haunted house, or a sunrise. Now we're getting closer to the real musical meaning, because we don't have a story to worry about while we're listening. You see all we have to think of is the general idea, and that's easier so we can concentrate more on the music and enjoy it more. For instance, take Beethoven's Sixth Symphony. Here is a wonderful piece, full of charming tunes and marvelous rhythms - driving, peaceful, happy - all kinds of things.

But in Beethoven's mind this symphony was somehow tied up with the idea of the countryside - farmers, brooks, shepherds, birds. So he called it the Pastoral Symphony - as you know, pastoral means anything to do with the country. At the beginning of the first movement he wrote the words: "Awakening of cheerful feelings on arriving in the country"; - and the music goes like this:

[PLAY: Beethoven - Pastoral Symphony]

It sure sounds happy, cheerful, pretty, all right. But these feelings, after all, could be happy for any other reason, too; supposing Beethoven had said "Happy feelings because my uncle left me a million dollars," or "Happy feelings because my bellyache went away" - he could still have written this happy music, and it would have been just as good, just as happy.

Now let's try something; let's change the title of this piece, and call it "Happy feelings because my bellyache went away" let's say, and let's listen to it with that in mind and see if it sounds any different.

[ORCH: Beethoven - Pastoral Symphony]

It's still the same happy music, whether it's about your tummyache or a trip to the country. The second movement Beethoven calls "By the Brook." And in this movement he's trying to describe or imitate or suggest the motion of the water in the brook.

[PLAY: Beethoven - Pastoral Symphony]

But supposing we call it "Asleep in a Hammock," and that the motion it is now describing is of the gentle rocking back and forth in a hammock instead of the water - let's see how the music would sound then.

[ORCH: Beethoven - Pastoral Symphony]

Doesn't change a thing, does it, whether it's water or a hammock swinging. It's the same lovely music.

Now one of the best pieces that paint pictures is by a Russian Composer called Mussorgsky and he wrote a piece called "Pictures at an Exhibition." What Mussorgsky did was to take a lot of pictures hanging on the wall in a museum and write music that he thought could describe them - in other words, to try and do with notes what a painter does with paint. But of course notes can't do what paint can do; you can't draw your nose with F sharps, you can't draw a building or paint a sunset with notes. But you can sort of try to do it. Anyway. Here's one of those pictures he tried to do it with — it shows children playing in a park; and what Mussorgsky did to make it sound like kids playing was to imitate the way children talk when they play games - almost like singing when you go in a game "allee allee in free, allee allee in free." There's a kind of tune you sing. Or when kids are taunting each other, making fun of each when they play, and go "Nya nya, nya nya." Mussorgsky took this nya-nya-nya-nya and watch how he uses it.

[ORCH: Mussorgsky - Pictures at an Exhibition]

Nya-nya-nya-nya - you see how he uses it. Almost to paint children with notes. Then there's another picture Mussorgsky painted with notes; of many little chickens not yet out of their egg-shells, who do a dance. Now listen to how he describes chickens in notes, the way he imitates their pecking and squawking.

[ORCH: Mussorgsky - Pictures at an Exhibition]

Then the finally, the last one of the series where he paints a big gate in the city of Kiev — a tremendous stone structure. Now you can see what Mussorgsky had in his mind, when you hear these great big strong chords, like pillars holding up those tons of stone.

[ORCH: Mussorgsky - Pictures at an Exhibition]

That made you think of a big gate, didn't it?

[KIDS RESPOND]

Okay, but only because I told you beforehand that you were supposed to think of a gate. If I'd told you to think instead of the Mississippi River flowing majestically down the middle of America, you would have had that in your mind when you heard those big chords. So again - there's the old answer; the picture that goes with music goes with it only because the composer SAYS so; but it's not really part of the music. It's extra.

Now we're going to take another giant step toward finding out our answer to "What music means". And this is a really big step; we're getting closer now to the answer! Because let's now forget about all the pieces of music that try to tell stories or paint pictures — we've had enough of that — and we're going to listen to music that describes emotions, feelings - like pain, happiness, loneliness, anger, love. I guess most music is like that; and the better it is, the more it will make you feel those emotions that the composer felt when he was writing. Tchaikovsky was a composer who always tried to do this - who always tried to have his music mean something easily recognized as emotional. Take this part of his Fourth Symphony:

[PLAY: Tckaikovsky - Symphony no. ]

I guess the best way to describe that would be by saying that it has the feeling of wanting something very badly that you can't have. Did you ever feel that you wanted something more than anything else in the world; and you said so, and they said "no, you can't have it," and you said again - "I want it!" And again they said no, and again you said, louder and more excited, "I want it!" and louder "I want it!" until it seemed that something would break inside you and there's nothing left to do but cry? Well, that's like this music. Listen.

[PLAY: Tckaikovsky - Symphony no. 4

with voiceover of "I want it."]

Then finally something breaks in your head

[PLAY: Tckaikovsky - Symphony no. 4]

and you cry. Now listen to the orchestra play it, and see if you don't feel something like those emotions.

[ORCH: Tckaikovsky - Symphony no. 4]

Pretty emotional stuff, isn't it? Now sometimes Tchaikovsky uses the same tune to describe two different emotions. For instance, at the beginning of his Fifth Symphony he writes this tune, which sounds sad and gloomy and depressed.

[ORCH: Tckaikovsky - Symphony no. 5]

Pretty impressive. But at the end of the symphony, in the last movement, he changes a couple of notes - what musicians call changing from minor to major (some of you know what that means) - and it all comes out joyful and triumphant, like some who has just made a touchdown and is the hero of the football game.

[ORCH: Tckaikovsky - Symphony no. 5]

Didn't you feel triumphant? Didn't that make you feel like the winner at least of a football game, maybe of a presidential election. Now we can really understand what the meaning of music is; it's the way it makes you feel when you hear it. Finally we've taken the last giant step, and we're there, we know what music means now. We don't have to know a lot of stuff about sharps and flats and chords and all that business in order to understand music; if it tell us something - not a story or a picture - but a feeling - if it makes us change inside, and have all those different good feelings music can make us have, then we are understanding it. And that's all there is to it. Because those feelings aren't like the stories and pictures we talked about before; they're not extra; they're not outside the music; they belong to the music; they're what music is about.

And the most wonderful thing of all is that there's no limit to the different kinds of feelings music can make you have. And some of those feelings are so special and so deep they can't even be described in words. You see, we can't always name the things we feel. Sometimes we can; we can say we feel joy, or pleasure, peacefulness, whatever, love, hate. But every once in a while we have feelings so deep and so special that we have no words for them and that's where music is so marvelous; because music names them for us, only in notes instead of in words. It's all in the way music moves - we must never forget that music is movement, always going somewhere, shifting and changing, and flowing, from one note to another; and that movement can tell us more about the way we feel than a million words can. Now here we're going to play you a tiny little piece by a modern composer named Webern who writes music that's so special in its sounds and in its meaning that a lot of people don't understand it at all and just call it crazy modern music. But I know that very often young people can understand this kind of music better than older people, so I'd like to take a chance and play it for you, crazy as it is. See what you think of it.

[ORCH: Webern - Six Pieces]

Pretty special stuff isn't it? You see if you even sneeze or cough you're liable to miss it. It's so delicate and so deep inside that you mustn't even breathe while it's going on. What did you think of it? Did you think it was ugly or was funny? Did you think it was pretty? Didn't it make you have feelings? Well, that's wonderful, that's just the wonder of music that it can make you have, different people have different kinds of feelings. For instance ... if I play a note on the piano, just one note and I hold it for a long time —

[PLAY]

— that has no meaning at all, has it. But let's say I play the note and them move to another one,

[PLAY]

— right away there's a meaning - a meaning we can't name, a sort of stretch, or a pulling, or a pushing, something like that, but it's there. The meaning is in the way those two notes move, and it makes something happen inside of you. If I move from that first note to another one

[PLAY]

— the meaning changes - something else happens inside of you - the stretch is bigger, somehow, and stronger. Now this note —

[PLAY]

— means one thing with this chord under —

[PLAY]

and it makes you fell a certain way, and it means something completely different with this chord under it—

[PLAY]

And it makes you feel another way. And with this chord under it,

[PLAY]

Or with this chord

[PLAY]

And each way, each different chord makes you fell a different way. Now what about these notes — do you know what these notes are?

[PLAY: Schuman/Rozsa - Dragnet Theme]

What's that?

[AUDIENCE RESPONSE]

Right! Well, they mean something exciting and spooky is going to happen, like "Dragnet", but if I took the same notes and just played them in a different way, they'll mean something else.

[PLAY: Schuman/Rozsa - Dragnet Theme]

Silly. Just light and silly, and they're the same notes.

So you see, the meaning of music is in the music, in its melodies, and in the rhythms, and the harmonies, and the way it's orchestrated, and most important of all in the way it develops itself. But that's a whole other program. We'll talk about that some other time. Right now, all you have to know is that music has its own meanings, right there for you to find inside the music itself; and you don't need any stories or any pictures to tell you what it means. If you like music at all, you'll find out the meanings for yourselves, just by listening to it.

So now, I want you to listen to a short piece without any explanation from anybody. I'm not going to tell you anything about it, except the name of it, and who wrote it. And you just all sit back and relax, and enjoy it, and listen to the notes, and feel them move around, jumping, and hopping, and bumping, and flashing, and sliding, and whatever they do, and just enjoy THAT without a whole lot of talk about stories and pictures and all that business. The piece we're going to play is by Ravel and is called "La Valse". I think you'll like it because it's fun to listen to — and not for any other reason, not because it's about anything. It's just good, exciting music.

[ORCH: Ravel - La Valse]

END

© 1958, Amberson Holdings LLC

All rights reserved.