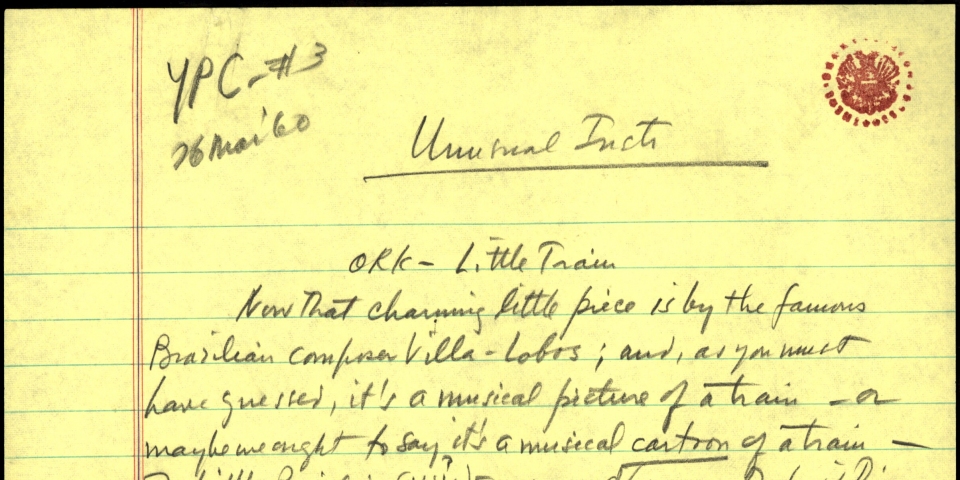

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsUnusual Instruments of the Past, Present & Future

Young People's Concert

Unusual Instruments of the Past, Present, and Future

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 27 March 1960

(ORCH.: VILLA-LOBOS - THE LITTLE TRAIN) (3:30)

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

Now that charming little piece is by the famous Brazilian composer -Villa-Lobos; and, as you must have guessed, it's a musical picture of a train - or maybe we ought to say it's a musical cartoon of a train - called The Little Brazilian Local. Of course, the first thing you'll wonder about this piece is: how does that composer get a regular, ordinary symphony orchestra to sound like a train? In fact, how does he get the orchestra to sound so peculiar in general-so new and different from the way the same orchestra sounds when it plays Beethoven or Brahms? Well let's see; because that's what we're going to be talking about today: unusual new sounds and old sounds, and the unusual instruments that make them. Well, one way Villa-Lobos imitates a train is by using a very unusual bunch of percussion instruments - (That's the noise making department over there) - special Brazilian folk-instruments that make odd little noises, in addition to the usual percussion instruments we ordinarily use, like the kettle-drum and snare-drum and cymbals, and so on.

For instance, he uses a thing called a Ganza, which is a sort of metal tube filled with pebbles; and when it's shaken it sounds like this:

(EXAMPLE: GANZA)

Then there's something called Chocalhos, another kind of rattle, which is wooden this time, with beans inside making a rattling noise like a maracas:

(EXAMPLE: CHOCALHOS)

Then there's the Raganella, which is a sort of ratchet, the kind you whirl around when you want to make a real racket on New Year's Eve:

(EXAMPLE: RAGANELLA)

And finally Villa-Lobos uses a Reco-reco, which is a saw-toothed sort of vegetable - a squash, or gourd, that you can scrape with a scraper, making this very South-American noise:

(EXAMPLE: RECO-RECO)

All these noisy things played together with the usual percussion instruments can make a sound very much like a little, tired train, trying to get started up a hill:

(PERCUSSION ALONE TO (2) )

But the really interesting thing is not so much what those unusual percussion instruments do, as what the rest of the orchestra does - the regular, plain old symphony orchestra of Beethoven or Brahms. Because here the composer uses the same instruments everyone else uses - to make train-sounds that are absolutely new and different. And they're all made with the same instruments we use at every concert - those four families we've always talked about on these programs the brass family, with its trumpets, trombones, and horns; the percussion family, with their various noise-makers; the wood-winds - flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons; and finally the string family - double-basses, cellos, violas, and violins.

That's the usual symphony orchestra, as we know it today. (ALL SIT) All right, but let's just see how Villa-Lobos uses these same violins to make train-music.

(VIOLIN I, BAR 3)

You see, that thin whistle-sound comes from playing the regular violin way up as high as it can go, and by having mutes placed on the strings to make the sound even thinner. Listen again:

(REPEAT; VIOLIN I, BAR 3)

Then we get another kind of whistle from the flute and clarinet - the same regular old flute and clarinet Beethoven used - by having them blow into their instruments in a way called flutter-tongue (SHOW) - and they sound like this:

(FLUTE AND CLARINET, BAR 5)

Then we hear the horns and trombone imitate the puffing and groaning of the train by sliding from one note to another - what we call glissando:

(HORNS AND TROMBONE - 3 BEFORE (3) to (3)

(Then we hear the squeaking and squealing (of the poor little train, as the (woodwinds play way up highs (WOODWINDS - 2 BEFORE (6) )

Now comes another whistle, more like a siren, as the woodwinds slide around in their qlissando:

(WOODWINDS - 4 BEFORE (8) to (9) )

And finally a tremendous warning whistle, made by everyone playing trills and scales as fast as they can:

(TUTTI: 6 BEFORE (10) to (10) DOWNBEAT)

And all these groans and whistles and squeals go on over a Brazilian samba-beat (SING) Which is luckily very much like the sound made by a train's wheels:

(LOW STRIN&S AND PIANO - (2) to (3) (DOWNBEAT)

So you see, most of these peculiar noises are really caused by the regular instruments of the orchestra, those unusual percussion things we heard before are only sort of trimming, extra Brazilian noises, * * op. cut

And now that you've discovered all the secrets of how Villa-Lobos makes his orchestra into a musical train, we're going to play this little piece all over again for you; and I think this time you'll be able to hear it with wide open ears, and really understand it - that is, understand how the composer makes the usual and unusual instruments play together to make a brand new orchestral sound. Here goes The Little Train again.

(ORCH: VILLA-LOBOS - THE LITTLE TRAIN)* (3:30) *CUT

Okay; so that's enough of the Little Train. But the thing we should learn from it is So we see that the most usual instruments can also make the most unusual noises. Now of course these modern instruments weren't always usual ones. What we call usual instruments these days are pretty unusual compared to what they used to be. They've changed a lot since the old days; and I'd like now to show you what some of them were like many years ago, way back even before Bach. But remembers these peculiar instruments you're going to hear from the past were the usual instruments of their own times; and the people who played them four or five hundred years ago, would sure be amazed to see what they've grown into in our time; they'd call our instruments pretty unusual.

For instance, take our modern clarinet (CLARINET - 1 NOTE) and Oboe (OBOE - 1 NOTE) These two instruments are very much alike; because they are both long tubes of wood with holes in them; but the clarinet is played by blowing on a single reed, or piece of cane, which is placed in the mouthpiece; while the oboe's reed is double - that is, there are two pieces of cane laid together, forming a mouthpiece by themselves. Do you hear the difference in sound? The single reed, round and full: ECU MOUTHPIECE (CLARINET) and the double reed, sharper and more ECU MOUTHPIECE (OBOE)

Now both these instruments are descendants of an old instrument called a shawm (SPELL) - which was a word that used to apply to all such wind instruments in general, no matter whether they had a single or a double reed. Now this word shawm was originally a Latin word, calamus, believe it or not - Calamus, meaning a reed; then it was changed a little by the French into chalumeau (SPELL), which was changed back by the Italians into the word salmo. and by the English into shalmey. Then the English, who love to shorten words anyway, shortened shalmey to shalm (SPELL), which can also be pronounced shalm, like palm or calm, and then finally, in good old British style, it became shawm and was even spelled that way - SHAWM. Now Ifm not trying to give you language lessons in Carnegie Hall; but it's important to know all this because the French chalumeau finally grew into what we know as the clarinet (PLAY) and the English shawm, grew into what we call the oboe. (PLAY).

Now we are very lucky to have with us today three real shawms those double-reed great-grandfathers of the oboe, and three friends of ours who actually know how to play them. (ENTER) Aren't they pretty? They are going to play an old Spanish dance; in fact, 400 years old - accompanied by a tambourine. 1 think you'11 be surprised at how powerful they sound. We always think of old-time instruments as soft and delicate - but not these shawms. Just listen.

(SHAWMS: DE LA TORRE - ALTA) (1:05)

Isn't that marvelous?

(INTRODUCES SECOND PIECE) CUT (2nd SHAWN PIECE) (:50)*

Hearing those instruments makes you feel as if you were really living hundreds of years ago. But now we're going to move forward in time about 100 years, and listen to a wonderful piece of music for brass instruments by the Italian composer Gabrieli. Now there's a special thing about this piece, which is called a Canzone, which really means a song - only it's not sung. It's played by two small groups of 4 brass instruments each: the two groups play separately, answer each other, or sometimes play together. Now here's what we're going to do: one of these brass groups will be modern - the regular trumpets and trombones from our Philharmonic; (THEY STAND) but the other group will be made up of, old instruments from Gabrieli's own time (ENTER) but again these instruments will be a high trumpet, called a cornetto in those days, and three old trombones (THEY ENTER) which were then called sackbuts. Aren't they beautiful instruments? Hold them up, so we can see them better. (MORE)

They'd be beautiful just to have around the house, as ornaments; but wait until you hear them. They're just as beautiful to listen to. Could we hear a note on that high cornetto? Now let's hear the sackbuts one at a time. (PLAY) [*And strangely enough, that's a brass instrument not made of brass, but of wood. Just figure that one out.] So now we will have a blending of the old and the new, as we join trumpet with cornetto, and trombone with sackbut, in Gabriel's Canzone for eight instruments.

(GABRIELI: CANZONE FOR EIGHT INSTRUMENTS. (2:50)

Isn't it fascinating to hear old sounds and new sounds side by side? It gives us such a clear, idea of the difference between olden times and our own times, just by hearing the sounds that were made then and now. That's really the best and most exciting way to know history: not just by studying about dates and battles and who was king of what in which century, but by coming close to the art of history - by looking at the pictures people painted in any certain period of history, or reading the poems they wrote, and hearing the music they heard. Then we can almost put ourselves in their place, and pretend we're living in those long-ago days; then we can really understand history - which is not just a dull subject in school, but an exciting way of knowing about what happened in our world before we were living in it. I remember that when I was a small kid I had no interest in how the world was before I was in it, and I think that's true of most kids.

But suddenly there comes a moment - maybe when you're 11 or 14 or 17 when you suddenly realize that there had been a big and interesting world going on for thousands of years before you were in it from the minute you realize this, and begin to want to know what this world was like, from that minute on, you're on your way to becoming a thinking person, a really educated person. So, because this is so exciting - this comparing of new and old sounds - we1 re going to do the same thing again, with other music, and with other unusual instruments. This time we're moving up again in history, to the l8th century, the time of Bach; and we're going to hear one movement from his 4th Brandenburg Concerto. Now this concerto was written for a group of instruments like this: a smallish string orchestra, violins, violas and cellos, a double bass, a harpsichord; and added to that, 3 solo instruments (ENTER) that play their own special parts: 2 flutes and a single violin. By the way, all these guests of ours who play old Instruments are members of a group called the New York Pro Musica that specializes in music of long ago.

Now the violins of Bach's time were very much like ours, only they had a much shorter neck (SHOW AND COMPARE), and they were played with a bow that was curved instead of straight, like ours (SHOW AND COMPARE), There are other differences in the way of playing, but I won't bother you with all that now, Then, the flutes of Bach's time were also different. The usual silver flute that we know (SHOW) was just beginning to be used in Bach's day; but the flutes that were mostly used then were what we would call recorders, played not horizontally (SHOW) but straight ahead just like a shawm, only without a reed in the mouthpiece. (SHOW) These recorder kind of flutes have a very different sound from modern flutes - much softer and not so brilliant. Now here's what we're going to dos we're going to play the 1st Movement of Bach's Concerto, again using these old instruments and our modern ones, sometimes one group and sometimes the other.

The two groups will just take turns, back and forth, and at the very end of the movement they'll all play together. Now just to make the difference really clear, we'll do it this ways when the old flutes and the old violin are in the saddle, there will also be the old harpsichord playing with them, and this old low instrument called a viola da gamba playing the lowest part. But when our modern THEY STAND flutes and violin take over we will use the modern piano instead of the harpsichord, and our modern cello instead of the old viola da gamba. Is that clear? I hope so I can hardly follow it all myself. Okay, here we go, on our see-saw of history, back and forth between the old and the new.

(BACH: BRANDENBURG- CONCERTO NO. 4 IN G. MAJOR, 1st MOVEMENT) (8:00)

So far, we've heard some pretty interesting sounds, old and new ones, but nothing really brand new. After all, the usual instruments of our modern orchestra have been around for a pretty long time; and even those funny percussion instruments we heard in the Brazilian train piece aren't exactly new instruments, even if they're unusual; they're folk instruments that have also been around for a long time. But what are really new instruments? The saxophone? No - it's been around for one hundred years, even before jazz was invented. The mellophone you hear in school bands? No - that's just another kind of French horn. No, the really new instruments are electrical ones, or rather, electronic ones. I'm sure there are lots of you who understand what that means. There have been hundreds of experiments going on in our time, trying to invent an electronic instrument that will make a sound, unlike anything ever heard before.

Composers are always wanting to make new sounds never heard before; and some of them have tried doing it with these new inventions. There's one such instrument called the Theremin which is used a lot in movie music, especially when they need a spooky effect, or someone is losing his mind. I'm sure you've heard it: it has a sort of ghostly, trembling sound; and that sound is made electronically, without even touching the instrument. Then there's an instrument with a keyboard called the Ondes Marteno {which also makes pretty spooky electronic sounds like this:

(TAPE DEMONSTRATION)}*

But the most important thing that's being done for new sounds these days is, of all things, the tape recorder. Imagine an instrument called a tape-recorder! But it is an instrument; only it doesn't need to be played with a bow or a stick or by blowing into it or hitting it; all you do is push a button and it's on its own.

It's amazing how many millions of sounds you can put on tape - a whole new world of sounds. Anything you want. There are two ways of putting sound on tape; one is by recording real sounds, like a bottle breaking, crash, tinkle, tinkle -and then play it backwards, so that you hear the tinkles before the crash itself. It's a weird new sound. Or you can take that same sound and play it faster or slower or higher or lower, again making a new sound.

(EXAMPLE)

That of course was lower and slower. And you can do these things with any other sounds talking or singing or stamping or coughing. Then the second way is to make artificial sounds you don't record a real sound and then change it; you actually record pure tone that is made by an electronic instrument called an oscillator. This is a very hard scientific business, and I don't know too much about it myself; but I've heard a lot of the sounds and they're really new and exciting.

Just listen:

(SERIES OF EXAMPLES)

That's what's called pure bone. Now we're actually going to play for you a whole piece using this strange instrument: A Concerto for Tape-Recorder and Symphony Orchestra. The music is by two composers - that's pretty unusual in itself. I guess one composer writes more for the machine and the other writes more for the human players, and then they get together and make single piece out of it. Mr. Ussachevsky is the one who is the tape specialist, (STANDS) and he will be operating the machine; and Mr. Luening is the other composer, and I guess he'll just he listening. (STANDS) This is really new music; in fact it's never been heard before anywhere. It was especially written for the New York Philharmonic to play on this program. And I warn you: it's way out. Here it is - Concerto by Luening and Ussachevsky for Tape-Recorder and Orchestra.

(LUENING-USSACHEVSKY - CONCERTO FOR TAPE-RECORDER AND ORCHESTRA) (10:00)

Wow! I feel as though I've been on a space ship somewhere around the moon -don't you? That music really takes us into the future. At least it starts us imagining what music could be like a hundred years from now. Who knows s maybe it will be all tape-music, which would put an awful lot of musicians out of work. But luckily we don't have that problem yet. Now just to bring you all back to earth from this space-music we've been hearing, we're going to wind up today's program with a little fun, a bit of dessert. This is also going to be an unusual sounds - at least it's an unusual sound for a symphony concert - the sound of a kazoo. (SHOW) There's nothing new about this instrument; I've played it for years, and it's the simplest instrument ever invented. All you do is take this piece of tin, which looks something like a cigar and something like a submarine, put it in your mouth, and sing into it. (SING A NOTE) You see, anyone can do it.

No lessons necessary, and no practicing either. (SING A TUNE) And this instrument has a lot of variety too, depending on who's performing, a man or a woman, a high voice or a low voice, a good voice or a bad voice, like mine. But today we have a great kazoo is t to play for us, a girl with a lovely voice, named Anita Darian. (ENTERS) Miss Darian will perform with us the last movement of a special concerto for kazoo and orchestra by the talented young American composer Mark Bucci. Mr. Bucci calls his piece "Concerto for a Singing Instrument", - but that's just a fancy way of saying what it really is: a concerto for kazoo. This is also the first performance anywhere of this remarkable composition. And I trust it won't be the last.

(ORCH. AND KAZOO: BUCCI - CONCERTO FOR A SINGING INSTRUMENT) (4:20)

END

© 1960, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.

Watch a video excerpt of "Unusual Instruments of the Past, Present & Future