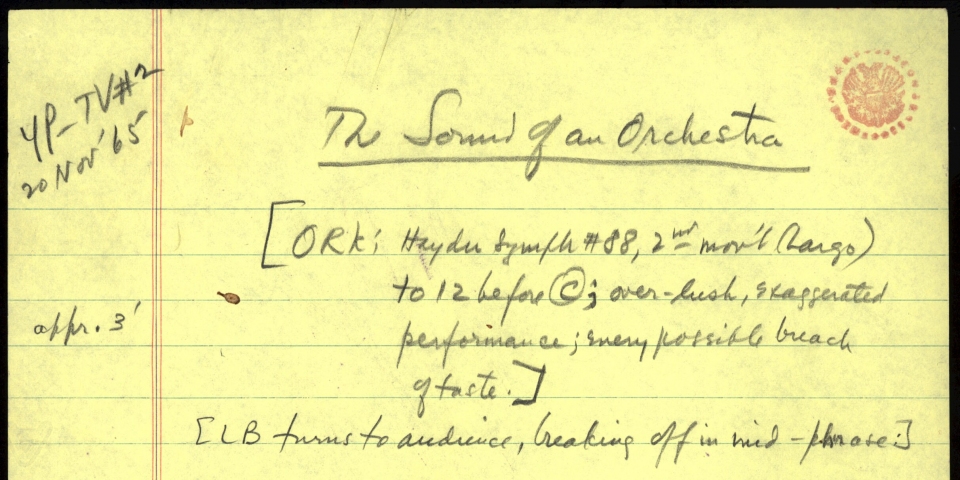

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsThe Sound of an Orchestra

Young People's Concert

The Sound of an Orchestra

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 14 December 1965

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

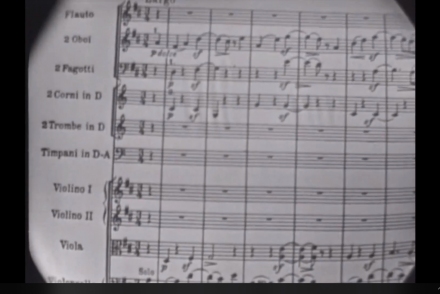

So you think that's beautiful—what you've just been listening to? Huh? Rich, luscious, expressive orchestral playing? Full of emotion? Great arching phrases? Singing silken strings? Throbbing oboes and flutes? Mighty brass and drums? You find it beautiful? Well, I've got news for you—it isn't. I don't mean the music itself—that's very beautiful, one of the most inspired movements Haydn ever wrote in all of his 104 symphonies, of which this movement is from his 88th. No, I'm not talking about the music; I'm talking about our performance, this particular performance which we have carefully prepared to show you exactly how this piece of music should not sound. Now you may have found the noises we've been making very pretty ones, perhaps even moving; but they are not the sound of Haydn. They are the sound of an orchestra showing off.

Now what do I mean by the "sound of Haydn?" After all, isn't the sound of any composer only the notes he puts down on the paper? Doesn't he then need a great orchestra to interpret those notes for him? Of course that's true; that's what great orchestras are for. But it is the job of the orchestra, and of its conductor, to interpret those notes as closely as possible to what we imagine the composer wanted—to make the kind of sounds we believe he heard in his mind when he wrote the music.

And that's not always easy to do, especially when you're dealing with a composer like Haydn, who wrote this music we've been playing almost two hundred years ago. What was his orchestra like? What kinds of sounds did it make? Well who knows, we can never really know; but we can make an educated guess. And this guesswork is the lifelong task of all performing musicians—orchestral, soloist, conductor, singers; constant study, research, and rethinking of music again and again, in order to recreate the sound of a composer.

Then why have I called this program "The Sound of an Orchestra"? I'll tell you why. Because a lot of people have a mistaken idea about the whole matter. I'm sure you've often heard people talk about the "sound" of this or that particular orchestra—what a special, unmistakable sound it has; how you can always recognize it, hearing it unannounced on the radio, or in the middle of the Sahara Desert, or whatever. But that's exactly what a great orchestra should not have—its own personal sound, piece after piece, year after year. Because if it always has its own sound, how can it ever have the composer's sound? No; the sound of a great orchestra is one that can change, at will from one composer's style to another, from Haydn to Brahms to Debussy to Stravinsky. Anything else is a sin of pride.

And that sin is just, just what we have been committing, right here before your eyes and ears, with this Haydn symphony. We have taken an elegant work from the eighteenth century, a graceful monument of the classical period, and turned it into lush, Juicy-Fruit music that might have been written a century later by a raving romantic. Now let me show you exactly how we've been doing this, so that later you can see what the proper sound of an orchestra ought to be.

The first, and major sin we've been committing has been the one of exaggeration. We have been exaggerating everything—phrasing, dynamics, vibrato, glissando, rubato—there's a string of fancy words for you. But they're really quite easy to understand. Take dynamics, for instance. That word dynamics simply means the degrees of loudness and softness with which we play music. And boy, have we ever been exaggerating those dynamics! Wherever Haydn has written "soft", we played "very soft", for "loud", we've been giving "very loud." Now the way "soft" is written down in music, as you may know, is by the letter p, which stands for piano (that's the Italian word for soft). And likewise, the Italian word for loud being forte, a composer indicates loudness by writing the letter f. All right, let's look at what Haydn wrote. He has written p, meaning soft, at the beginning of the opening phrase, and he has given his melody to the solo cello and the solo oboe, an octave apart.

Now on that high note, a very expressive one, as you heard, Haydn has written the letters sf, which stand for sforzando, meaning that that one note should get an accent, an extra-heavy attack. But that sign sf occurs in a soft phrase, as we know from the letter p, at the beginning; so, as you can understand, the accent should be a soft accent—in spite of the fact that it has the loud letter f in it in the sf sign. Even professional musicians sometimes confuse the sf sign with the f sign, and always play the accent loud; but you can certainly see that if the general dynamic is p, for the whole phrase, and the sf applies to one note only, then that accent has to be made in terms of softness, not loudness. And what were we doing? All the wrong things.

First of all instead of p, soft, we were playing double-p, very soft,—it's called pianissimo—to start the phrase; and when we landed on the high note, we landed with a bang—exaggeration. Then, what's even worse, we connected the soft place with the loud place by making a crescendo, which means a growing of volume, where Haydn hadn't written any crescendo at all. So that the phrase came out sounding like this:

Terrible. And it's even worse on the second phrase, which goes higher:

Exaggerating. And it's worst of all on the third phrase, which goes higher still:

Very expressive, but all wrong. So, you see, we have been exaggerating not only the dynamics, but the phrasing as well. We have taken Haydn's gently curved phrases, and turned them into Arches of Triumph, each one higher than the last. Very bad taste. Now listen to the next phrase, which is for the strings alone.

All right, what was so bad about that? Everything. First of all, there is the whole problem of the vibrato—another Italian word that refers, as you might guess, to vibrating. Vibrato is what happens when you see a string player wiggle the fingers of his left hand on the strings. Mr. Munroe, could you let us see that wiggle, please?

Can you all see that? Very good, the wiggle. As you can imagine, that wiggling causes whatever note he's playing with the bow to wiggle as well—that is, to vibrate, changing its pitch very slightly and rapidly—like this.

You hear that? Now why does he do that? Because vibrato can make a note sound very expressive. Let's hear that same note with no vibrato at all.

Nice, clean, dry, sound. All right, now let's hear it with just a touch of vibrato—a very narrow one.

Beautiful. Now a big wide one, but slow.

You hear that difference? Now a wide one, but fast.

You hear that difference? You see, there are all kinds of ways to make vibrato, and they're all very expressive of something; but the question is, which one is expressive of Haydn? All right, let's test it. Mr. Munroe, would you play us the vibrato you used when you played the first phrase.

Do you approve of that?

No, of course, because it's too sentimental. It's like those singers who drive you crazy with the tremolo in their voices:

It's an unbearable sound. All right, Mr. Munroe, let's hear the phrase with what you consider the proper vibrato.

That's more like it. A small, rapid vibrato. Very elegant indeed. And now that we know so much about vibrato, let's listen to that same string-phrase again, in all its sentimental wrongness, using the big, slow, wide vibrato which would be great for music written one hundred years later, but not for Haydn.

Beautiful, you say? Ghastly. And it's not only the vibrato that was wrong. All the instruments have been playing in their highest positions, where the vibrato shows up most garishly. Let me explain that to you. You see, a single violin note can be played in different positions, depending on what string you're playing it on. Mr. Corigliano, would you play us, let's say, the note C in a low position on the A string?

Good, now, let us hear the same note in a high position on the D string.

You hear the difference? The higher the position of the hand on the string, the more wobbly that vibrato is going to sound. And therefore more, shall we say, "emotional." Which is a dandy sound for Wagner or Mahler, but not for Haydn. And to make it all still worse, all our string players have been sliding from note to note—which is called glissando—sliding with one finger—it's another sentimental device. Mr. Corigliano, would you play us a few notes of that tune glissando?

It's a perfect technique for the Supremes, or for certain Italian opera singers. But not for Haydn.

And then to make everything completely terrible, to top it off, I've been conducting this phrase with very free changes of tempo—that's called rubato—rushing forward and then slowing up, suddenly, which is another great romantic trick, properly used, and in its place; but this place isn't it.

Terrible, isn't it? So, all together, what with vibrato, glissando, rubato, sforzando, crescendo—we've turned poor Haydn into quite a mess. And for what? To what end? Simply to show off the rich sound of an orchestra, instead of the true sound of a composer.

Of course you realize that I've been exaggerating terribly myself, in order to show you these things as clearly as possible. You don't actually often hear this sort of distortion from our good orchestras—but then again, sometimes you do. For instance, one of the more common sins against music of this classical period is the one of using the full orchestra for a piece that calls for only about half of it. And we've also been doing that right here before your eyes. Haydn wrote his symphonies for an orchestra that performed either in small music rooms, or in the palace of a count or prince, or sometimes even in a modest-sized theater in London. But he never had in mind the stage of Philharmonic Hall! We have here in our orchestra, for example, sixty-seven string-players alone. Now Haydn may have used as many as twenty, if he was lucky; and so should we, if we were in a small hall. But being where we are, we must use a somewhat larger string section—let's split the difference and say forty; but certainly not sixty-seven! So the first thing we must do if we're ever going to play this music well, is to reduce the orchestra by about twenty-five string players. Now, in fact, we have been overstocked not only on strings, but on the winds and brass, as well. So that means that nine more splendid musicians have to go. I'm awfully sorry but, goodbye, gentlemen.

And now perhaps we are finally going to be in a position to play this piece by Haydn. We are going to pick up near where we left off—which was just around the middle of the movement—and this time we are going to try and play it in the best possible style. And that does not mean a dull, dry performance, by any means; we hope that the music will have as much sensitivity, tone-quality, shading, line, elegance, and dynamic contrast as it needs—but just as much as it needs: not more.

Now we've spent a long time on that one movement of a Haydn symphony, but I think it was worth it, if only you've learned to hear the difference between exaggerated sentimentality and real feeling, especially in eighteenth-century music. But now, as we move ahead into the nineteenth century, you'd think: OK, at last we can begin to show off the big modern orchestra, all stops out, no holds barred. Here's romantic music, at last, in full dress; and now we're entitled to make our juicy romantic sounds. But it's not that simple: even in the nineteenth-century music there are all kinds of differences in the sounds an orchestra should make, depending on which part of the nineteenth century, on the nationality of the composer himself, and especially on the composer—always the composer. He comes first.

Take Beethoven, for instance—a very special genius; and part of his genius was a kind of gigantic roughness, an almost crude quality that expressed itself sometimes in rage, sometimes in humor, and sometimes in wild celebration. Now the famous opening of his Fifty Symphony, for example, is a defiant, angry utterance. And the orchestral sound it demands should be rough and angry, too.

You see what I mean? It can't be rough enough. And later on in the same symphony there's another famous place, in the middle of the third movement, where the cellos and double-basses roar out a crude sort of peasant dance, half-joking, and half-threatening:

Rough enough for you? Or think of the last movement of Beethoven's seventh symphony—that mad, leaping carnival dance:

A frenzy like that just can't be delivered by an orchestra without playing rough. You have to dig into the instruments in a special way—which is Beethoven's way, and only Beethoven's way. You'd never use that kind of sound, or tone, in music by Brahms, for instance, no matter how giant-like or angry he ever gets. Take this spot from Brahms's first symphony for example—and this is as angry as Brahms ever gets:

Now, you see, it's a completely different sound; rugged, yes, but not rough. With all its rage and whatever it is still rich and warm in a way peculiar to Brahms, but not to Beethoven.

So you see, it's not just a simple matter of having one kind of sound for the eighteenth century and another for the nineteenth. With each nineteenth-century composer—Beethoven or Brahms or Berlioz or St. Saens, or Tchaikovsky—there are different sounds that must be made. And this applies just as much to the wind-players as to the strings; they also have their different vibratos—faster, slower, wider, narrower; they also change their sounds for different composers.

Now one of the best ways to understand how this is done is in terms of French music versus German music. Nineteenth-century French music, from Berlioz right up to Debussy, has certain colors, or tone qualities that must be supplied by the orchestra—and they're very different colors from the German ones. Let's see what some of them are, and how they're different. Have you ever heard a piece by Debussy called Ibéria? It's gorgeous music about Spain, full of delicious Frenchy-Spanish sounds. Now just listen to this tiny bit from the end of the second movement, which is called "Perfumes of the Night":

Now do you hear the sound of that oboe solo? A typically French sound, very fine, not too rich or thick, with a well-controlled fast vibrato. That's a sound of which our solo oboe-player, Mr. Gomberg, is a master. But he must also be a master of other sounds, too, if he is not going to spend his whole life just playing Debussy. So listen to how German he can become in this famous oboe solo from Brahms's first symphony, and see if you can hear how different he makes the instrument sound:

Now that is rich and thick and warm—and German. Almost like a different instrument from the one in Debussy, isn't it? But it's the same instrument, the same oboe, only adapting its sound to the nature of the composer's music, this time, Brahms. Now let's get French again; back to Ibéria, where, immediately after that spot we heard before, there is a sweet, fading section describing the end of that perfumed night and the gradual appearance of the dawn. You begin to hear faint church-bells, and the distant echo of a street-musician—night sounds and morning sounds mixing together in a strange dreamlike atmosphere.

What a collection of subtle colors that is! First there was the flute, pale and mysterious in the early light:

Again, a typically French sound: thin, transparent, delicate. And then there was a violin solo, also thin and delicate.

And then there was those distant bells, which are imitated by the French horns, like echoes:

And that street musician, a trumpet, far off in another part of town:

Now all these mingle together to make a magic moment, between night and day, neither night nor day—a suspended moment of transition to the brilliant last movement which is coming called "The Morning of a Festival Day." And now we begin to hear the throbbing sounds of distant guitars, in a sort of Spanish march rhythm:

And now it is full, bright daylight; the festival is on. And over the marching guitars we hear two clarinets blaring out a raw folk tune, shrill and piercing and carefree:

Now before we play this whole exciting movement for you, I'd just like to plunge all these musicians back, for a minute into the other world—the German world of Brahms. Now just as Mr. Gomberg could switch his oboe like that from the Debussy-sound to the Brahms-sound, so can our Mr. Baker do the same with his flute. He too is a master of many sounds, as are all the great artists who make up this orchestra. You remember that we left Mr. Baker pale and wan in his perfumed Spanish dawn; and now listen to how different he sounds in Brahms:

Rich, strong, full—the exact opposite of his Debussy-sound, which was thin and delicate. Both sounds are equally beautiful, but they are very different; as they must be for two such different composers.

And Mr. Corigliano, whom we last heard being thin and delicate: here is the same artist, the same violin in the Brahms symphony:

A whole other violinist—warm, glowing with the sound of Brahms. And that French horn that we last heard echoing faint church-bells—listen to Mr. Chambers become Brahms:

How fat he's grown! And that distant wandering trumpet, our street-musician: look at Mr. Vacchiano now:

You wouldn't recognize him, would you? And then, all those plucked strings, that we last heard imitating tinny guitars a minute ago—listen to them as they pluck Brahms:

What a difference! And why do they sound so different in Brahms? Because this time they're not just plucking the strings with their right hand, they're making vibrato at the same time with their other hand, thus producing this dramatic, and rich Brahmsian effect.

Hear that? You see, there's more than one way to pluck a string.

And what about that happy-go-lucky clarinet we last heard squealing away like a folk-instrument? Here is the very same Mr. Drucker, only changed into a serious German named Brahms:

A miraculous change, isn't it? They are all miraculous changes, and when all the musicians change together in favor of one composer or another, then you have beautiful and proper orchestral playing.

So where does that leave us with this so-called "sound of an orchestra?" Nowhere. There's no such thing—or at least, there shouldn't be. All that matters is the sound of the composer. So now I invite you to listen to the sound of Debussy, the last movement of Ibéria, called "The Morning of a Festival Day."

You know, many people think that when it comes to music of our own century there's no longer any problem about what kind of sounds should be made. Modern music is modern music; you play the notes and hope for the best. But that's not true at all. All music of any period, including our own, calls for special treatment, according to who the composer is.

For instance, Stravinsky, the greatest composer in the world today. There's a sound in much of Stravinsky's music which is special: clean, sharp, unromantic, and dry as a bone. Now don't be misled into thinking that such a sound isn't pretty, or musically exciting; on the contrary, it can be extremely charming and even invigorating. And to show you what I mean, I'd like to play you a short piece from Stravinsky's ballet The Story of a Soldier. This work is written for seven players only, who all have to play in one style, all soloists, but all playing with that same clear, dry sound, so as to produce the effect of absolute clarity, like a perfect photograph. Or maybe I should say more like a comic strip: you know how extra-clearly the lines are drawn in Dick Tracy or Terry and the Pirates—more clearly even than a photograph, or even of living people. And that's how this piece should sound. In a way, it is like a comic strip, a sort of pop art that prophetically got written almost fifty years ago.

Now how do we make these comic-strip sounds? Well, first of all, take the solo violin who is one of the seven players, he has to play practically without any vibrato—sharp and exact and clear, like this:

And so must the bassoon and the clarinet:

And so must everyone else, even the drummer. Imagine, there are even different ways of handling drums so as to produce the proper sound for each composer. Take the bass drum, for instance, as used by Verdi in his great Requiem. It should be the most enormous, resonant drum you can find, a real whopper, one that can shake your very soul.

But the bass drum as used by Stravinsky—the same instrument—in The Story of a Soldier is a whole other matter—light, dry, and not very resonant, more like the kind a jazz drummer uses, with a pedal attached.

Dry and clear—every instrument must sound the same in this piece. And even when the music gets a bit on the sweet side, it's still the sweetness of a comic strip—a bit sentimental, not quite on the level, and more for the sake of fun than true emotion. Like this passage:

That's the sound of Stravinsky—one of his sounds, anyway. And now let's hear this great piece of pop art—the "Royal March" from The Story of a Soldier.

There's one more side to the sound of modern music that I think you'd like to know about, and that's the sound American music. In this department there are very special sounds to be made, particularly jazzy ones. For instance, you all know George Gershwin's exciting piece An American in Paris? Do you? I guess you do. Well, there's a trumpet solo in it that's sort of a Charleston; goes like this:

Now imagine that tune played in the Brahms manner, with a rich German sound; it might come out like this.

It's ridiculous. And it sounds equally ridiculous played in the Debussy manner, with a light French sound:

No, the sound has to be an American one—direct and strong, yet casual,—it's rather subtle and with a feeling for the rhythm, which is not just a string of equal notes,but slightly unequal.

That makes it American: And that's the Gershwin sound.

That's the sound of Gershwin. Now another typically American sound that's hard for some symphonic players to grasp is the sound of country fiddling. If you've ever been to a square dance you'll know right away what I mean. Now the great American composer Aaron Copland has borrowed this sound in his ballet Rodéo or Rod_o: I guess you pronounce it. Listen to that sound:

Now here again we have the same problem that we had in Gershwin; these violinists here are trained in the classical tradition; and if they see a string of notes like those we just heard, all looking exactly alike, they're probably going to play them all exactly alike in the great tradition of Bach; like this:

Now using that Bach style, the Rodeo music by Copland would sound like this:

And that's not at all what we're after. We want the sound of country fiddles. And that means that the notes mustn't be all alike, but again, as in the Gershwin Charleston, slightly unequal.

That's the country-dance spirit, free-wheeling, easy; a typically American sound. And to get that sound, the violins simply have to stop being violins and change into fiddles.

So there we are. Haydn, Beethoven, Brahms, Debussy, Stravinsky, Gershwin, Copland—each one has his sound, or sounds; and it's our job as a symphony orchestra to deliver them to you—not our sound, but their sounds.

And so to end this program, we're going to play for you that exciting little hoe-down from Rodéo or Rodeo; and we trust that what you'll be hearing will not be the sound of the Philharmonic, but the sound of Aaron Copland.

END

© 1965, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.