AboutConductorColumbia Records

John McClure and Leonard Bernstein the studio; Photo by Don Hunstein (1963), courtesy of Sony Classical

John McClure and Leonard Bernstein the studio; Photo by Don Hunstein (1963), courtesy of Sony Classical

Overview

Leonard Bernstein recorded over 500 compositions with Columbia Masterworks Records, now Sony Music Entertainment, between 1956 and 1979, 455 of which were recorded with the New York Philharmonic. Bernstein signed his first long-term contract with Columbia on April 2, 1956, regarding services as piano soloist, as conductor, and as commentator, and signed his final contract for a new recording on May 11, 1979 for a recording of Prokofiev's Fifth Symphony with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra.

Bernstein's entire recording legacy with Columbia, under the Sony label, can be explored in the Discography with links to download to your favorite listening service.

In addition to musical recordings, hundreds of moments were captured by photographers, especially Don Hunstein, during his time with Columbia. Sony has graciously allowed us to integrate these photos throughout the website, which we hope will heighten the experience

Bernstein vs. The Studio

Recording Lenny the Hard Way

by John McClure

(as printed in the 1993 Spring issue of Prelude, Fugue & Riffs)

At the risk of waxing sentimental, I invite you to join me in a reminiscence on my early recording days with Lenny. To do this, let's go back: back to the dawn of recording history, say, to about 1959, when digital still meant "finger-operated"; when Lenny was Music Director of the New York Philharmonic and under contract to Columbia Records; back to when he was slim and boyish and I was a green, young record producer, to a time when we used to have rites of passage called recording sessions, marathon-like events of seven or eight hours that went on until someone finally ran out of gas.

I had come to this enviable hotseat from a musical/harpsichord/engineering background. It helped that I was a good bluffer; when crises arose that were outside my ken, I learned on the job while maintaining an air of studied casualness. I had started out at an engineering job with Columbia Records, and was brought into the Masterworks Department in 1957 by its director David Oppenheim, Lenny's recording producer and friend. Oppenheim gave me a once-in-alifetime, sink-or-swim opportunity to organize a recording project in Hollywood with Bruno Walter involving a new process called stereo. Luckily, I sawm.

In 1959, Oppenheim announced his departure for the greener fields of television, leaving Schuyler Chapin, a Columbia Artists Management graduate, and myself to run the department. His gift to us before leaving was a recording contract with Mr. Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic that was to last almost 20 years. In that time, Lenny and I made about 200 records together, in ten countries, 16 cities and 26 different recording locations.

My frist encounter with LB and the Philharmonic came about in 1959, at Symphony Hall, Boston. Schuyler Chapin had scheduled the first recording under this contract to coincide with LB and the orchestra's return to the US from a triumphant tour of the Soviety Union. The orchestra disbanding for vacation the day after their Boston concert, so this was our only chance to record. For me, it was an unknown conductor and orchestra in an unfamiliar hall. A serendipitous blend of luck, good microphone placement and inspired orchestral playing resulted in classic recordings of the Shostakovich Fifth Symphony and Copland's Billy the Kid. With a happy conductor as a bonus, we were off on the right foot.

Our subsequent recording locales in New York wound from the St. George Hotel in Brooklyn (where we might have stayed longer if the Jehovah's Witnesses hadn't bought the hotel for their world headquarters) to Manhattan Center on 34th Street to Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center, with occasional forays into Columbia's 30th Street studio. Recording in the Grand Ballroom of Oscar Hammerstein's opera house, which became Manhattan Center in a seedier incarnation, was rarely a pleasure, although in mid-winter, when the heat was on and the hunmidity reduced, it produced quite thrilling results. But these came at a considerable human cost.

Woe to the poor maestro as the excessive liveness of this florid Egytian/Deco magnificence forced him (for reason of ensemble) to conduct actual beats instead of subtle phrases. Woe to the poor record producer forced to bring his mikes closer and closer to placate the distraught maestro, who demanded presence and clarity from this greasy swamp of reverberation. Woe, too, to all present and involved, since this situation had the potential of putting the maestro in a foul mood where, even though renowned for his taciturn forbearnance, he just might let slip a mild remonstrance or grimace that the naive onlooker might misinterpret as extreme personal displeasure.

Mind you, even at the best of times, all symphonic recording sessions, with their $200-a-minute tension, start out with a varying degree of panic. And it was often difficult to take into account the string player's need to warm up and our own need to reposition microphones to adjust for that specific day's reverberation time. Even when the hall was "behaving," it wasn't easy work. Lenny's idea of a good orchestral perspective was what he heard on the podium—in the thick of it. It frustrated him that you, the listener, safe in your tenth row seat, were quite out of harm's way. He wanted the music to leap at you, assault you, caress you the way it did him. Even when I had completed a recording I felt was too present, Lenny would, in post-production, push me to raise this phrase, or highlight this section. There was no getting round him: the music-rabbi didn't just play the music, he taught it.

For thirty years we struggled over this note, that perspective. We did our best. And while life with Lenny was often nerve-wracking, it was also vivid, educational, warm, stimulating and exhausting. His absence leaves a big hole in all our lives.

John McClure was a recording engineer and record producer for Columbia Masterworks Records who worked with Bernstein for more than 30 years, winning a Grammy Award for Bernstein: Symphony No. 3 'Kaddish' in 1965.

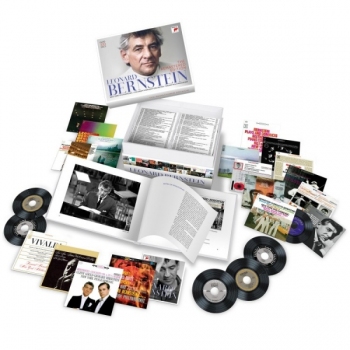

Leonard Bernstein Remastered

For his centennial in 2018, Sony Classical released Leonard Bernstein's classic American Columbia recordings, remastered from their original 2- and multi-track analogue tapes. This remastered 100 CD set has allowed for the creation of a natural balance (for example, between the orchestra and solo instruments) that brings the quality of these half-century-old recordings, excellent for their time, up to the standards of today's audiophiles. In addition, there has been a meticulous restoration of some earlier masterings in which LP surface noise was too rigorously eliminated at the expense of the original brilliance.

This comprehensive display of the legendary American conductor's unparalleled dynamism and versatility is offered in a single package. Many of Bernstein's most memorable and critically acclaimed interpretations are brought together here. Learn more